- newsletter

- Extra Credit

How to help students who are ‘Perpetual Analyzers’

These students need help with coming to conclusions.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2019. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

How to help students who are ‘Biased Jumpers’

How to help students who are ‘Confused Fact-Finders’

Guide students toward better critical thinking

TOPICS

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series of articles to help you explore student thinking, and how critical thinking is taught and learned, to better enable you to help your students thrive in today’s complex business and accounting environment. The first article provides an introduction to the series, while the second and third discuss the “Confused Fact-Finder” and “Biased Jumper” stages of critical thinking development.

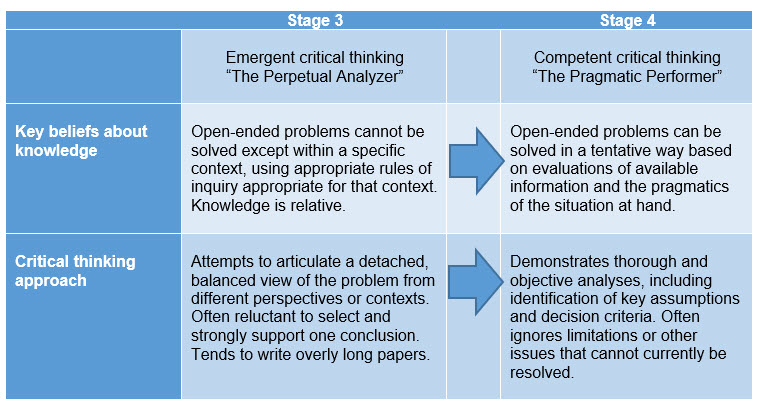

This series of articles provides specific recommendations for helping students improve their critical thinking within accounting courses. By directly addressing the beliefs about knowledge and learning that students hold at each stage of their critical thinking development, accounting educators can increase both students’ motivation to learn critical thinking skills and the effectiveness of the learning methods they use. This article addresses students at the third stage of development, which I nicknamed the “Perpetual Analyzer.”

“Perpetual Analyzer” thinking and how to recognize it

At the “Perpetual Analyzer” stage of development, students demonstrate many desirable critical thinking skills. They are capable of understanding problems in a complex way, are aware of their own limitations and biases in understanding a problem, and actively seek to understand others’ viewpoints. They can logically and qualitatively evaluate the evidence and assumptions that underpin different perspectives. A minority of the students I have taught in undergraduate and master-level courses have demonstrated this pattern of thinking.

Although the reasoning skills of Perpetual Analyzers allow them to draw logical conclusions within a given perspective, they have great difficulty prioritizing factors to reach and defend a single “best” solution to a problem when more than one viable option exists. In the introduction to this series, I told a story about a partner of a CPA firm who stated, “We can’t afford to have our people sitting around, thinking all day.” I would guess that the partner was referring to people operating at the Perpetual Analyzer stage, who tend to get stuck in the process of analyzing and exploring the problem. Their difficulty arises in part because they have given up their previous “Biased Jumper” ways of thinking and have not yet developed a way to make decisions that controls for personal bias.

How can you recognize students who are operating at the Perpetual Analyzer level of thinking? Below are common signs.

The student:

- Is unable to establish priorities for judging across alternatives

- Is reluctant to select and defend a single overall solution as most viable, or selects a solution but unable to express adequate support for its superiority over other solutions

- Writes overly long paper in attempt to demonstrate all aspects of analysis (unable to prioritize the most important issues and factors)

- Jeopardizes class discussions by getting stuck on issues such as definitions

Source: Wolcott, S. K. (January 26, 2006). Steps for Better Thinking Performance Patterns [Online]. Available: www.WolcottLynch.com. Based in part on information from Reflective Judgment Scoring Manual With Examples (1985/1996) by K. S. Kitchener and P. M. King. Grounded in dynamic skill theory (Fischer and Bidell, 1998; Fischer and Pruyne, 2002).

Because students’ beliefs about knowledge drive their critical thinking approaches, our challenge as faculty members is to alter their underlying beliefs about how the world works. Here are some suggestions for how to do this.

How to help Perpetual Analyzers develop

The most effective approach is to help these students move to the next-higher pattern of thinking, which I’ve nicknamed the “Pragmatic Performer.” At this next stage, students act in a practical way to reach and defend conclusions.

(Note: These patterns are based on Stages 5 and 6 in the reflective judgment model developed by P.M. King and K. S. Kitchener. For details, see my freely available Faculty Handbook: Steps for Better Thinking. For a copy, send an email to swolcott@WolcottLynch.com.)

Perpetual Analyzers try to remain as objective as possible while they evaluate a problem from different perspectives. While objectivity is desirable for good critical thinking, it can interfere with students’ abilities to choose and defend a single best solution. Thus, Perpetual Analyzers exhibit “analysis paralysis”: They delve more deeply into detailed (and often unimportant) aspects of the problem as they avoid reaching a conclusion. They might also cite a conclusion without giving it adequate support. These students need to learn how to identify priorities they can apply for evaluating across competing solutions/perspectives within the context of the problem.

Teaching/learning recommendations

Here are some ways to teach students how to prioritize information when addressing an open-ended problem. Encourage them to:

- Clarify the most important issues and factors in a situation. Faculty often assume that students who can thoroughly and objectively analyze information can readily identify the most important issues, risks, evidence, stakeholders, and so on in a given situation. However, remaining objective while also establishing priorities requires the ability to move back and forth between the details of a problem and the overall situation. In homework assignments and classroom discussions, it is helpful to have students consider questions such as these: Who are the key stakeholders in this situation, and which issues are most important to those stakeholders? For this problem, which details and evidence need to be addressed, and which are less important — and, therefore, should be set aside? Why are the priorities for this situation different from those for another similar situation?

- Choose and explain assumptions and decision criteria. Because Perpetual Analyzers are trying to maintain objectivity and avoid bias, they often have difficulty establishing priorities that lead to appropriate assumptions and decision criteria. You can help these students by having them compare and contrast the terms bias and priority and by identifying each characteristic in sample responses to an accounting problem. It is also helpful for these students to gain greater comfort through practice. For example, you can ask students to identify reasonable assumptions or decision criteria as a homework problem, and then have students compare and discuss the reasons for their choices in small group and/or whole class discussions. As Perpetual Analyzers gain greater experience considering alternative sets of assumptions and decision criteria, they will become more comfortable making their own choices.

- Adapt communications for different audiences. Perpetual Analyzers not only have difficulty prioritizing details when analyzing a problem but also have difficulty prioritizing information when communicating to an audience. Ask students to practice visualizing and modifying communications for different audiences when writing about open-ended problems. It is also helpful to divide assignment requirements into two parts. In the first part, ask students to address the needs of an audience within a (relatively short) paper length limit. In the second part, ask students to explain how they decided which information to include/exclude in the first part. I have found that this assignment design reduces student stress about reducing details in the first part of the assignment and provides me with information in the second part for giving students useful feedback.

Look for the next article in this series, which will address issues in the typical accounting classroom, populated by students operating at different stages of critical thinking development.

Susan Wolcott, CPA, CMA, Ph.D., is a founder of WolcottLynch, which conducts research and develops educational resources for critical thinking development. She has taught accounting courses at seven universities and is currently a visiting professor at the Indian School of Business. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact senior editor Courtney Vien at Courtney.Vien@aicpa-cima.com.