- newsletter

- Extra Credit

Guide students toward better critical thinking

Learn about the stages of critical thinking to help accounting students develop skills needed for professional success.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2019. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

A problem-based learning project for accounting classes

Help students embrace emerging technologies

TOPICS

When I first began focusing on the development of student critical thinking skills in the early 1990s, I discussed ideas for a research project with the partner of a CPA firm. I recall being quite surprised when the partner stated, “We can’t afford to have our people sitting around, thinking all day.” I don’t believe that a partner would say the same thing today. While productivity no doubt continues to be important, today’s accountants are increasingly called on to address new types of problems in complex environments.

Unfortunately, as critical thinking research indicates, most college students graduate with only some critical thinking skills. This means that they also lack the critical thinking skills required by the accounting profession — which is expected to require even more critical thinking ability in the future.

The bottom line is that we need to help our accounting students close the gap between their current critical thinking skills and the skills they will need for professional success. How can we do this?

In this article series, I will provide specific recommendations for helping students improve their critical thinking within accounting courses. In this introductory article, I will provide a working definition of critical thinking and describe the “stages” of critical thinking that most college students will pass through. In subsequent articles, I will explain two of the stages in greater detail, discuss why students at each stage address critical thinking tasks in a specific way, and offer suggestions for creating more effective learning activities. These activities are designed to help students progress from one stage of critical thinking to the next.

How should we define ‘critical thinking’?

There is no universally accepted definition of critical thinking. Because different accounting educators are likely to have different ideas about this topic, I will begin with a definition. The Foundation for Critical Thinking provides several definitions of critical thinking, including the following description that is highly consistent with what is required of a professional accountant:

A well-cultivated critical thinker:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively;

- comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem-solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism.

Notice that this description holds the critical thinker to very high standards. It not only includes the process of analyzing information to form a logical conclusion, but it also requires the thinker to be self-aware, to test ideas against standards, to communicate and work effectively with others, and to seek improvement in light of inherent personal weaknesses.

The big takeaway for accounting educators is that critical thinking requires students to not only apply accounting knowledge correctly, but also to learn how to deal with ambiguous and complex problems and to adopt a mindset that enhances the quality of their work.

The stages of cognitive development

Not all accounting students start or finish college with the same level of critical thinking ability. In fact, most undergraduates have reached one of three stages of cognitive development. At each of these stages, students hold different underlying beliefs about knowledge. In turn, these beliefs influence how students respond to tasks that require critical thinking and can hinder the development of their critical thinking skills. By directly addressing students’ underlying beliefs, accounting educators can increase both students’ motivation to learn critical thinking skills and the effectiveness of the learning methods they use.

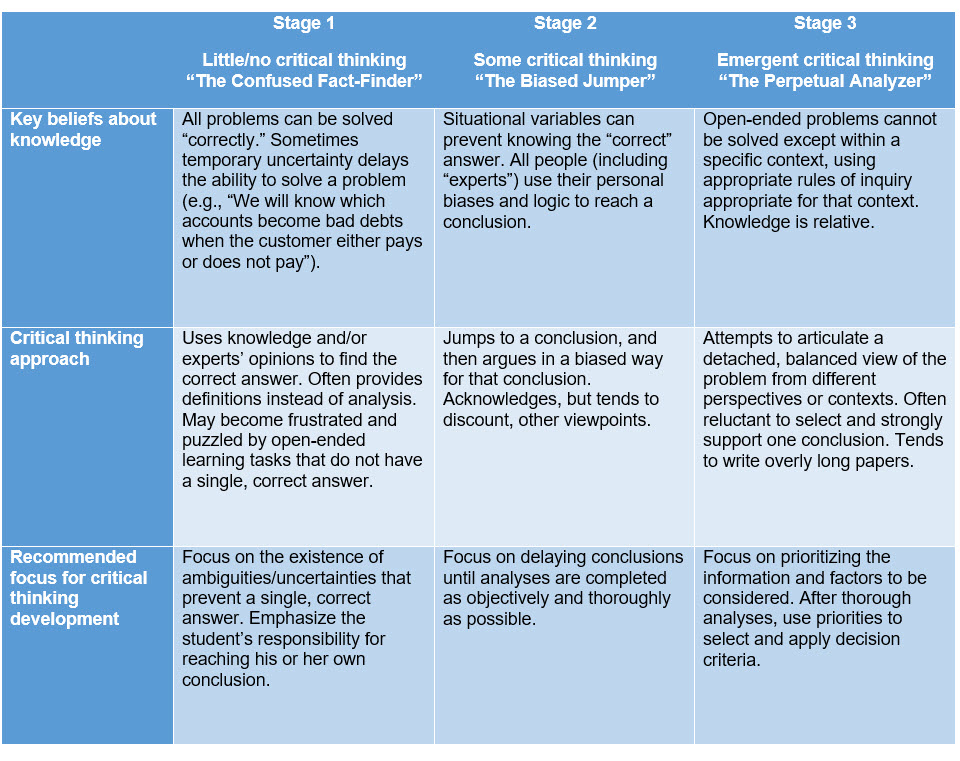

The three stages can be described as follows:

- Little/no critical thinking (“The Confused Fact-Finder”)

- Some critical thinking (“The Biased Jumper”)

- Emergent critical thinking: (“The Perpetual Analyzer”)

These are the most common stages students exhibit throughout the undergraduate experience. About half of first-year students will be in the first stage, and most graduating students will have reached the second stage. Only a minority of students will have reached the third stage at the time of graduation, but educators should still be aware of it because it represents the next step they can help students achieve.

In the table below, I briefly summarize these three thinking patterns, the beliefs about knowledge that undergird them, and key recommendations for the focus of teaching and learning. In upcoming articles in this series, I will address each of the three patterns of thinking in greater detail and present specific teaching and learning ideas to help your students develop stronger critical thinking skills.

(Note: These patterns are based on Stages 3, 4, and 5 in the reflective judgment model developed by Karen Kitchener and P.M. King. For details, see my freely available Faculty Handbook: Steps for Better Thinking. For a copy, send an email to swolcott@WolcottLynch.com.)

Remember — the accounting profession is evolving rapidly. In the past, it was satisfactory to focus accounting courses primarily on technical knowledge and theory. Over time, accounting education has evolved to be more practical, focusing on hands-on and project-based educational models. What is needed in the future is a greater emphasis on making business decisions in an ambiguous, nonlinear environment. The evolution of the CPA will depend on how readily accounting professionals can achieve the ambitious definition of critical thinking described earlier.

The purpose of this series is to help you explore student thinking, and how critical thinking is taught and learned, to enable you to help your students thrive in today’s complex professional and business environment.

Susan Wolcott, CPA, CMA, Ph.D., is a founder of WolcottLynch, which conducts research and develops educational resources for critical thinking development. She has taught accounting courses at seven universities and is currently a visiting professor at the Indian School of Business. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact senior editor Courtney Vien at Courtney.Vien@aicpa-cima.com.