- newsletter

- Extra Credit

How to help students who are ‘Confused Fact-Finders’

Try these tips to help students accept different points of view.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2019. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

Guide students toward better critical thinking

A problem-based learning project for accounting classes

TOPICS

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles to help you explore student thinking, and how critical thinking is taught and learned, to enable you to better help your students thrive in today’s complex business and accounting environment. See the first article for an overview of critical thinking and the three most common patterns of thinking exhibited by college students.

This series of articles provides specific recommendations for helping students improve their critical thinking within accounting courses. In the introductory article, I described the three most common “stages” of critical thinking. By directly addressing students’ beliefs that underlie each stage, accounting educators can increase both students’ motivation to learn critical thinking skills and the effectiveness of the learning methods they use. This article addresses students having little or no critical thinking ability, a stage I have nicknamed the “Confused Fact-Finder.”

‘Confused Fact-Finder’ thinking and how to recognize it

Research in higher education indicates that approximately half of first-year undergraduate students have little or no critical thinking abilities. Students at this initial stage of development tend to seek single correct answers to problems and become confused by open-ended learning tasks. I refer to this pattern of thinking as the Confused Fact-Finder stage.

How can you recognize students who are operating at the Confused Fact-Finder level of thinking? Below are common signs of this thinking pattern:

- Does not seem to “get it”; recasts an open-ended problem having multiple viable solutions as one having a single “correct” answer

- Insists that professors, textbooks, or other experts should provide the “correct” answer

- Expresses confusion or futility

- Inappropriately cites textbook, “facts,” or definitions

Source: Wolcott, S. K. (January 26, 2006). Steps for Better Thinking Performance Patterns. Available at WolcottLynch.com. Based in part on information from Reflective Judgment Scoring Manual With Examples (1985/1996) by K.S. Kitchener and P.M. King. Grounded in dynamic skill theory (Fischer and Bidell, 1998; Fischer and Pruyne, 2002).

Because Confused Fact-Finders believe that all problems can be solved correctly, they are highly resistant to the idea that they must reach their own conclusions. Why, after all, would mere students’ conclusions make any sense if experts know — and can tell them — the answers? These students might mistakenly believe that you are trying to trick them when you ask for their opinion. Their seemingly illogical responses, however, are completely logical when viewed from their perspective and their belief that all problems have one right answer.

Because students’ beliefs about knowledge drive their critical thinking approaches, our challenge as faculty members is to alter their underlying beliefs about how the world works. Here are some suggestions for how to do this.

How to help Confused Fact-Finders develop

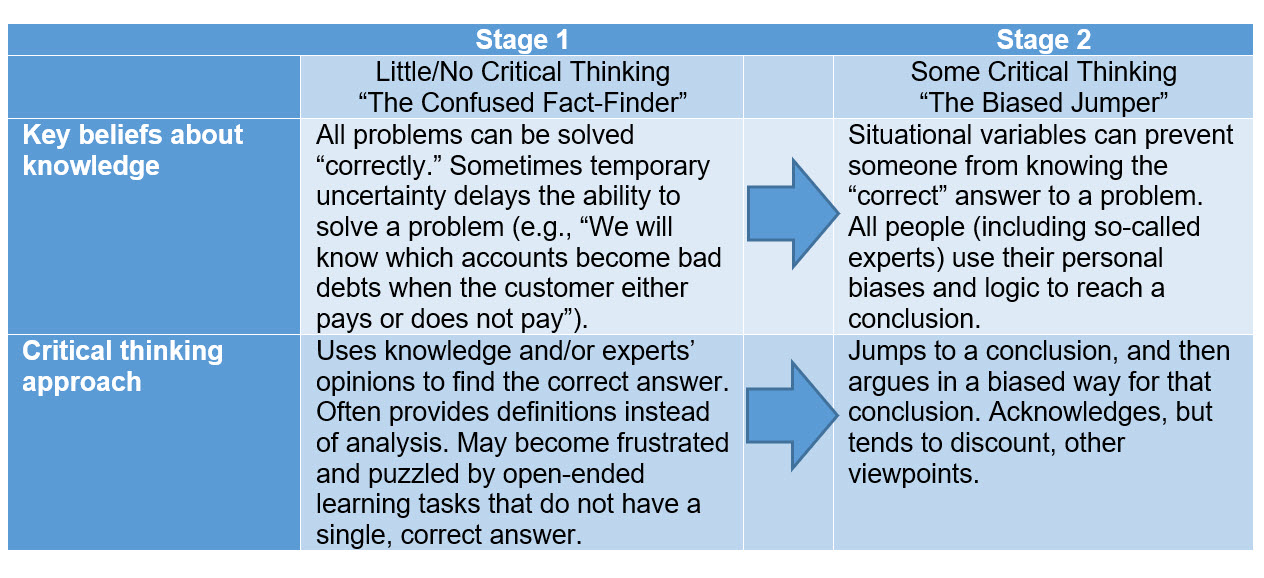

The most effective approach is to help these students move to the next-higher pattern of thinking, which I’ve nicknamed the “Biased Jumper” phase, in which students “jump” to conclusions they then defend with biased reasoning. This idea is illustrated in the following table.

(Note: These patterns are based on Stages 3 and 4 in the reflective judgment model developed by P.M. King and K.S. Kitchener. For details, see my freely available Faculty Handbook: Steps for Better Thinking. For a copy, send an email to swolcott@WolcottLynch.com.)

To help students make this transition, you need to focus on their underlying beliefs about knowledge. In particular, students need to recognize the existence of ambiguities/uncertainties that can lead to more than one viable answer to a problem. At that point, they can then be convinced that not all problems have a single correct answer. In turn, this realization helps them recognize the need to reach their own conclusion rather than to rely completely on experts (such as the professor and the textbook).

Teaching/learning recommendations

Here are some ways to teach students how to recognize the existence of uncertainties:

- Discuss different reasons for uncertainty. Find opportunities to discuss uncertainties in the material you are teaching. In an introductory financial accounting course, for instance, you can readily discuss uncertainties in conjunction with topics such as bad debts, depreciation and amortization, contingent liabilities, and interpretation of ratios. In an introductory management accounting course you could discuss uncertainties about cost behavior, relevant costs for decision-making, budgets, and interpretation of variances.

- Read about and discuss conflicting theories, opinions, and viewpoints. Students need to learn how to distinguish between problems having a single correct answer versus those having multiple viable solutions. Reading about and discussing conflicting theories, opinions, and viewpoints can help students learn to recognize each type of problem, which, in turn, will help them adopt an appropriate approach.

As students develop an understanding of uncertainties, they will be ready to develop simple critical thinking skills such as the following:

- Distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant information. Students often have difficulty distinguishing between information that is relevant to solving a problem and that which is not. They need to practice addressing problems that include both types of information, and developing an understanding of uncertainties will help them recognize which pieces of information matter for a given purpose or decision.

- Being able to list potential issues, viewpoints, and solutions. Before students can identify and analyze alternatives, they must first learn how to recognize issues, alternative viewpoints, and solution options from the information that they are given. A useful exercise is to have students read a well-written student paper and identify the issues discussed, the supporting evidence, and the conclusion. Although this type of assignment might seem simplistic, it can be very beneficial to students at this stage of critical thinking.

- Begin to use evidence to support conclusions. Once students learn that some problems are open-ended and have no single correct solution, they need to assume the responsibility for reaching conclusions. They should be encouraged to form their own opinion and to provide evidence/arguments to support it. Students at this level tend to use only limited evidence to support their opinions, and they often rely too much on personal opinion compared to other forms of evidence. They also tend to ignore or discount evidence supporting other conclusions. Although these students are not likely to demonstrate sophisticated analysis, they can benefit from exposure to the evidence and arguments used by students having stronger critical thinking skills.

Look for the next article in this series — which will address the “Biased Jumper” — for more critical thinking teaching and learning ideas.

Susan Wolcott, CPA, CMA, PhD, is a founder of WolcottLynch, which conducts research and develops educational resources for critical thinking development. She has taught accounting courses at seven universities and is currently a visiting professor at the Indian School of Business. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact senior editor Courtney Vien at Courtney.Vien@aicpa-cima.com.