- news

- AUDITING

How to maintain independence in audits of insured depository institutions

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2018. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

Auditing Standards Board proposes changes to attestation standards

What to know about engagement quality reviews (SQMS No. 2)

Change at the top: PCAOB will feature new chair, 3 new board members

TOPICS

Federal banking regulators are charged with safeguarding the financial stability of the federally insured banking system.

In this regard, Section 36 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (FDI Act) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC’s) implementing regulations (Part 363) are generally intended to facilitate early identification of problems in financial management at insured depository institutions (IDIs) with total assets above certain thresholds.

Currently, Part 363 requires an IDI with consolidated total assets of $500 million or more as of the beginning of its fiscal year to have an annual audit of its financial statements performed by an independent public accountant, and requires an IDI with consolidated total assets of $1 billion or more as of the beginning of its fiscal year to have the same independent public accountant audit the IDI’s internal control over financial reporting (ICFR).

The FDIC has determined that it is in the public interest for independence standards to apply uniformly to all independent public accountants that provide these services to IDIs subject to Part 363. To achieve this objective, Part 363 requires auditors to comply with all the independence standards applicable to both nonpublic and public IDIs that are established by the AICPA, the SEC, and the PCAOB rather than to comply with these standards on a selective or exclusionary basis.

This article discusses the independence requirements applicable to IDIs subject to Part 363, how they impact the auditor, and areas of the rules that have challenged auditors in recent years.

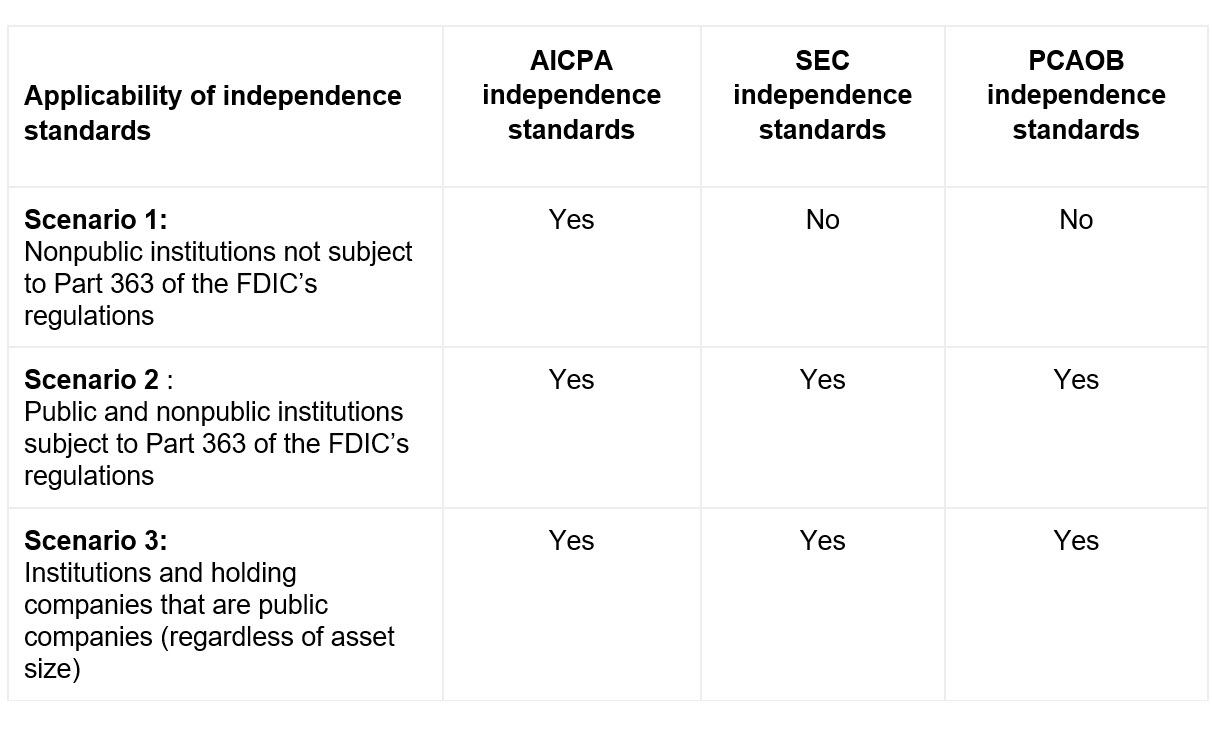

The table below summarizes the independence requirements applicable to IDIs:

Some practitioners have struggled with the application of SEC and PCAOB independence rules to their nonpublic audit clients (Scenario 2 in the table above), which for nonpublic IDIs is driven by asset size rather than entity type. Questions about these requirements include:

Do SEC and PCAOB rules apply if the IDI or the IDI’s holding company is a nonpublic company?

Yes, for IDIs with $500 million or more in assets, the more restrictive SEC and PCAOB independence requirements apply even if the IDI or its holding company is a private company that is neither registered with the SEC nor an issuer of securities.

Do SEC and PCAOB rules apply if the auditor has no SEC audit clients and is not registered with the PCAOB?

Yes, the more restrictive SEC and PCAOB requirements apply even if the audit firm has no SEC or issuer audit clients and is not registered with or inspected by the PCAOB.

The impact on audit firms

The FDIC has incorporated the AICPA’s, SEC’s, and PCAOB’s independence rules by reference in Part 363 (§363.3(f)) as a means of strengthening the auditor’s independence for IDIs that pose the greatest risk to the FDIC insurance pool. Therefore, auditors working in this space must educate themselves and their staffs about independence rules they may not otherwise be required to apply in their engagements.

To the extent that any of the rules within any one of the independence standards (AICPA, SEC, and PCAOB) is more or less restrictive than the corresponding rule in the other independence standards, Part 363 requires auditors to comply with the most restrictive rule, or portion(s) of a rule. Auditors with even a cursory knowledge of the independence rules know how diverse these rules can be — but not in all areas. For example, many of the personal independence requirements are quite similar.

Examples of SEC and PCAOB independence rules that are stricter than the AICPA rules include:

- Rules on performing certain nonaudit services for audit clients. Impermissible nonaudit services under SEC rules include bookkeeping and financial statement preparation, services involving confidential or aggressive tax positions, internal audit services, and personal tax compliance services for certain key executives and their families.

- Rules on contingent fee arrangements for certain tax-related work.

- Rules on business relationships with the audit client.

- Rules on use of indemnification clauses in audit engagement letters.

- Rules on audit partner rotation and compensation.

- Rules on audit committee oversight of the auditor. The SEC requires preapproval by the audit committee of all services provided by the external auditor, as well as annual communications by the auditor to the audit committee regarding independence issues.

Limitation-of-liability provisions

In addition to Part 363, the FDIC, at times working with other federal agencies, has issued interagency policy statements (also known as Financial Institution Letters, or FILs) addressing various concerns. In 2006, the agencies issued the Interagency Advisory on the Unsafe and Unsound Use of Limitation of Liability Provisions in External Audit Engagement Letters (the Advisory).

Regulators were concerned that contractual terms limiting the audit firm’s liability may weaken the auditor’s accountability, objectivity, and performance, which reduces the regulators’ ability to rely on the audit and raises safety and soundness concerns. Notably, the Advisory applies to all audits of IDIs, regardless of asset size, public or nonpublic.

Thus, even IDIs not subject to Part 363 must comply with the Advisory. For IDIs subject to Part 363, in 2009, the FDIC added Section 363.5(c), which requires IDIs’ audit committees to ensure that audit engagement letters and any related agreements for services to be performed under Part 363 do not contain any prohibited limitation-of-liability provisions.

The Advisory applies to contracts between the auditor and the IDI for financial statement audits, audits of ICFR, and attestations of management’s assessment of ICFR. It specifically bars agreements that:

- Indemnify the auditor against third-party claims.

- Hold harmless or release the auditor from liability for claims that the IDI might assert.

- Limit the legal remedies available to the IDI.

Exception for punitive damages

Provisions that waive the right of IDIs to seek punitive damages from the auditor are not treated as unsafe and unsound under the Advisory. However, agreements by IDIs to indemnify their auditors against third-party damage awards, including punitive damages, are deemed unsafe and unsound under the Advisory.

One caveat: To enhance transparency and market discipline, IDIs that agree to waive claims for punitive damages against their auditors should consider disclosing the nature of these arrangements in their annual proxy statements or other public reports.

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR)

Auditors may use alternative-dispute-resolution (ADR) agreements and jury trial waiver provisions in engagement letters only if they do not incorporate limitation-of-liability provisions. The provisions must be commercially reasonable and provide a fair and equal process for all parties, e.g., neutral decision-makers and appropriate hearing procedures. Auditors should not coerce their clients to agree to ADR.

As noted in the Advisory:

The Agencies have observed that some financial institutions have agreed in engagement letters to submit disputes over external audit services to mandatory and binding alternative dispute resolution, binding arbitration, other binding non-judicial dispute resolution processes (collectively, ‘‘mandatory ADR’’) or to waive the right to a jury trial. By agreeing in advance to submit disputes to mandatory ADR, financial institutions may waive the right to full discovery, limit appellate review, or limit or waive other rights and protections available in ordinary litigation proceedings.

Auditors should be aware that any provisions that limit or waive an IDI’s rights and protections available in ordinary litigation proceedings may lead to impaired independence.

The Advisory differs from the “Indemnification of a Covered Member” interpretation of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct (ET §1.228.010), which allows an auditor to be indemnified for liability and costs resulting from management’s knowing misrepresentations. However, practitioners should know that under the AICPA Code’s “Indemnification and Limitation of Liability Provisions” interpretation (ET §1.400.060), failure to comply with the Advisory is considered an act discreditable to the profession.

Where firms have struggled

As presented by the FDIC’s chief accountant (Division of Risk Management Supervision) at the 2016 AICPA National Conference on Banks & Savings Institutions, some noted problem areas for independence have included:

Indemnification/limitation-of-liability clauses in engagement letters. The FDIC staff has observed a resurgence in auditors’ use of indemnity and liability-limiting clauses in engagement letters that do not comply with the Interagency Advisory and Section 363.5(c) and violate the AICPA Code’s “Acts Discreditable Rule” (ET §1.400.001). Recall that the restrictions apply to all IDIs regardless of size or nature of the company, that is, an auditor may not limit their liability when auditing an IDI under the $500 million asset threshold.

PCAOB Rule 3526 independence letters. Some auditors are not issuing the annual PCAOB Rule 3526 independence letter to the client’s audit committee and discussing independence, as required under PCAOB rules. Section 363.3(f) clearly requires auditors to apply AICPA, SEC, and PCAOB rules, even if the auditor does not have any SEC issuer audit clients and is not registered with the PCAOB.

Employment relationships with audit clients. The FDIC staff has also noted instances of employment relationships causing independence issues. For example, SEC independence rules require a one-year “cooling off” period when a member of the audit team joins the client in a financial reporting oversight role, but some firms have not observed the “time out” period. Also, a firm member’s simultaneous employment at the audit firm and the client taints independence under AICPA, SEC, and PCAOB rules.

Prohibited nonaudit services. SEC rules have long prohibited auditors from preparing the client’s books and records, yet the FDIC staff has observed this in recent years. Staff has also noted instances where auditors performed loan reviews for their clients that were tantamount to internal audit outsourcing services, which are also prohibited. Remember that any amount of nonaudit services that leads to “self-auditing” impairs independence; there is no materiality threshold under the SEC’s rules. The staff has also observed firms’ not complying with the PCAOB rule that restricts firms from providing personal tax services to persons in financial reporting oversight roles at their clients (e.g., CEO, CFO, or treasurer).

Failure to monitor $500 million asset threshold. Since application of Part 363 hinges on the IDI’s asset size, failure to monitor when a client will hit that threshold and become subject to the annual audit and reporting requirements of Part 363 can lead to independence impairment.

For example, assume that a nonpublic IDI engages a firm to audit its financial statements for periods prior to the IDI becoming subject to Part 363 when its consolidated total assets were below the $500 million threshold. Also assume the auditor provided one or more nonaudit services (i.e., the auditor prepared the IDI’s financial statements and complied with the applicable AICPA independence rules) that would be prohibited under the SEC’s and PCAOB’s independence rules during those prior periods.

Then, as of the end of its 2017 fiscal year and the beginning of its 2018 fiscal year, the IDI’s consolidated total assets were $500 million or more and it became subject to Part 363. Since Section 363.4(a) requires an IDI’s Part 363 Annual Report to contain audited comparative financial statements, and audited financial statements were prepared for the IDI prior to it becoming subject to Part 363, the IDI’s Part 363 Annual Report for fiscal 2018 must include audited comparative financial statements.

The independence rules (AICPA, SEC, and PCAOB) require the auditor to be independent through the audit and professional engagement period. Therefore, when auditing the 2018 financial statements, the auditor must comply with the SEC and PCAOB rules in addition to the AICPA rules. However, since the firm has already performed prohibited nonaudit services in 2017, the audit firm is not considered independent and no longer qualifies to audit the 2018 financial statements.

Ramifications of noncompliance

As just illustrated, failure to meet the requirements of Part 363 can lead to a situation in which the FDIC will not permit a firm to audit its client. If an independence violation is discovered after the audit has been performed, a reaudit may be necessary.

Unfortunately, not all independence violations are fixable. Further, in egregious situations, the FDIC has the power to remove, suspend, or debar a practitioner from performing audit services under the FDI Act. If another federal banking agency (the Federal Reserve Board or the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) or the SEC or PCAOB removes, suspends, or debars a CPA from practice, FDIC regulations provide for automatic, similar action on its part.

Questions on independence and limitation-of-liability provisions

The FDIC staff encourages IDIs and their independent public accountants to consult with the FDIC’s Office of the Chief Accountant when issues arise regarding auditor independence and limitation-of-liability provisions in external audit engagement letters. To facilitate the resolution of these issues, the following information should be provided:

- The name and address of, and the contact information for, the IDI and the auditor;

- The names of the audit partner and other technical resources consulted, such as national office personnel;

- Timing considerations such as pending Part 363 filing deadlines;

- A copy of the audit engagement letter, including attachments;

- For independence issues at IDIs subject to Part 363, a copy of the written communication with the audit committee concerning independence (PCAOB Rule 3526);

- Detailed information regarding the specific facts and circumstances regarding the independence and/or limitation-of-liability issue;

- The specific independence and/or limitation-of-liability questions raised;

- The conclusions reached on these questions by the IDI and the basis for those conclusions;

- The audit committee’s views on the independence and/or limitation-of-liability issue; and

- The conclusions of the IDI’s auditor with respect to the independence and/or limitation-of-liability issue.

After considering the information provided, additional information may be requested.

Correspondence regarding auditor independence and/or limitation-of-liability matters can be mailed to the FDIC’s Chief Accountant, Division of Risk Management Supervision, 550 17th Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20429. Alternatively, the information can be emailed to Part363@fdic.gov.

The independence rule

(In FDIC implementing regulations)

Section 363.3(f): Independence. The independent public accountant must comply with the independence standards and interpretations of the AICPA, the SEC, and the PCAOB. To the extent any of the rules within any one of these independence standards (AICPA, SEC, and PCAOB) is more or less restrictive than the corresponding rule in the other independence standards, the independent public accountant must comply with the more restrictive rule.

Additional resources on this topic include:

- fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/part-363.html

- fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2009/fil09033a.html

- fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2006/fil06013.html

- fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2003/fil0321.html

— Catherine R. Allen (callen@auditconduct.com) specializes in ethics and independence through her consulting firm at Audit Conduct LLC in Rocky Point, N.Y. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Ken Tysiac, a JofA editorial director, at Kenneth.Tysiac@aicpa-cima.com or 919-402-2112.