- feature

- AUDITING

How to prevent late-stage engagement quality review surprises

Find out how to get EQ reviewers involved early and comply with audit-quality standards.

Related

What to know about engagement quality reviews (SQMS No. 2)

Change at the top: PCAOB will feature new chair, 3 new board members

How AI is transforming the audit — and what it means for CPAs

TOPICS

Imagine the final stages of an audit engagement are due in the next few days. During this concluding phase, you anxiously await forthcoming review points from the engagement quality (EQ) reviewer. The engagement is substantially complete; you simply need EQ reviewer approval. You may need to address a few review points, but you already performed the heavy lifting. Completion is a foregone conclusion, right?

Wrong. The EQ reviewer will not sign off because the concurring review reveals major deficiencies that will cause you to miss the deadline and may even prevent the issuance of the report.

This engagement suddenly turned sour. Sure, your firm’s quality management (QM) gatekeeper served the intended purpose by preventing a nonconforming engagement. But this late-stage revelation threatens the firm’s relationship with the client and may impair its reputation. Even worse, the firm could be exposed to litigation or other undesirable outcomes.

This scenario could have been prevented.

Professional standards require EQ reviewer approval before the audit report is issued, but this does not mean the EQ reviewer must remain offstage until the waning moments of the performance. Professional standards permit firms to tailor the nature, timing, and extent of the engagement quality review based upon quality risks and significant judgments. Earlier EQ reviewer involvement would have provided more time to address EQ reviewer observations and might have provided resources for the engagement team.

Firms often schedule the EQ reviewer’s concurring review for the late stages of an engagement. However, this may not be the best timing, especially if the reviewer identifies thorny circumstances that prevent or delay approval. Late-stage hurdles introduce stressors that can jeopardize client relationships and may even spawn legal, regulatory, and ethical complications.

Proactive practitioners exercise discretion regarding the nature, timing, and extent of EQ reviewer involvement. Professional standards offer flexibility that preserves a reviewer’s objectivity while preventing unpleasant, last-minute surprises. Firms can circumvent ugly outcomes by extending an early invitation for the EQ reviewer to join the party.

THE EQ REVIEWER ROLE

Quality of audit, review, compilation, and attestation engagements has long been a mainstay for accounting firms. Even before the AICPA overhauled QM expectations by issuing Statement on Quality Management Standards (SQMS) No. 1, A Firm’s System of Quality Management, firms were required to implement engagement quality control systems to provide reasonable assurance that the reports were appropriate for particular circumstances and that the firm and its personnel complied with professional standards and legal or regulatory requirements.

The notion of a concurring, objective review also is not novel. However, the AICPA did innovate by issuing SQMS No. 2, Engagement Quality Reviews, which clarifies expectations regarding the appointment of EQ reviewers and their responsibilities (see “Engagement Quality Reviews: What Auditors Should Know,” JofA, Dec. 9, 2024). Firms were required to implement these new standards by Dec. 15, 2025. With this deadline in the rearview mirror, practitioners have a perfect opportunity to consider the EQ reviewer’s role.

Ultimately, an EQ reviewer’s concurring review does not diminish an engagement partner’s responsibilities but offers “an objective evaluation of the significant judgments made by the engagement team and the conclusions reached thereon” (SQMS No. 2, ¶13) in concert with the firm’s system of QM in accordance with SQMS No. 1. Because the EQ reviewer is required to remain objective, the appointed reviewer cannot be a member of the engagement team and cannot make decisions or fulfill responsibilities of the engagement team. Importantly, the engagement partner may not release the engagement report until the EQ reviewer has approved its issuance.

THE SCOPE OF EQ REVIEWER PROCEDURES

Given the diversity of accounting practices, the provisions of SQMS No. 2 are necessarily scalable. Although firms may specify procedures, the scope ultimately will be influenced by quality risks. Important matters for an EQ reviewer to consider include, but are not limited to, engagement complexity, entity size, client characteristics, risk assessments, identified deficiencies, interactions with engagement personnel, and other contextual considerations. Moreover, the EQ reviewer may need to dynamically update procedures in response to evolving circumstances.

Detailed review of individual workpapers and granular analysis is not the EQ reviewer’s job. Rather, the EQ reviewer typically fulfills a broader role, much like the top-down approach of an engagement partner (but without inserting themselves into the fray of actual engagement performance). An EQ reviewer is required to evaluate significant judgments, discuss major conclusions, broadly assess subject matter, and ultimately approve the issuance of the firm’s report.

Even though professional standards require EQ reviewer approval before issuing the report for an engagement selected for an EQ review, this does not mean that the quality review must occur during the final stages of an engagement. In fact, QM standards explicitly explain that “frequent communication between the engagement team and engagement quality reviewer throughout the engagement may assist in facilitating an effective and timely engagement quality review” (SQMS No. 2, ¶A27). Therefore, firms have flexibility regarding the nature, timing, and extent of EQ reviewer involvement.

However, there is a warning in the footnote of this permission slip. The firm is required to take care that the EQ reviewer’s involvement does not become so extensive that they make decisions on behalf of the engagement team. An EQ reviewer must be impartial in both fact and appearance, a notion emphasized by Kevin Patterson, CPA, assurance market leader for BDO in Detroit, who characterizes a concurring reviewer as “the main judge and gatekeeper from an audit quality perspective.” Paragraph A12 of SQMS No. 2 explains that self-review, familiarity, self-interest, and intimidation threats could compromise a reviewer’s objectivity. Therefore, EQ reviewers, partners, and engagement teams must walk a tightrope to prevent surprises while preserving the EQ reviewer’s objectivity.

ENGAGEMENT PERFORMANCE IS A BALANCING ACT

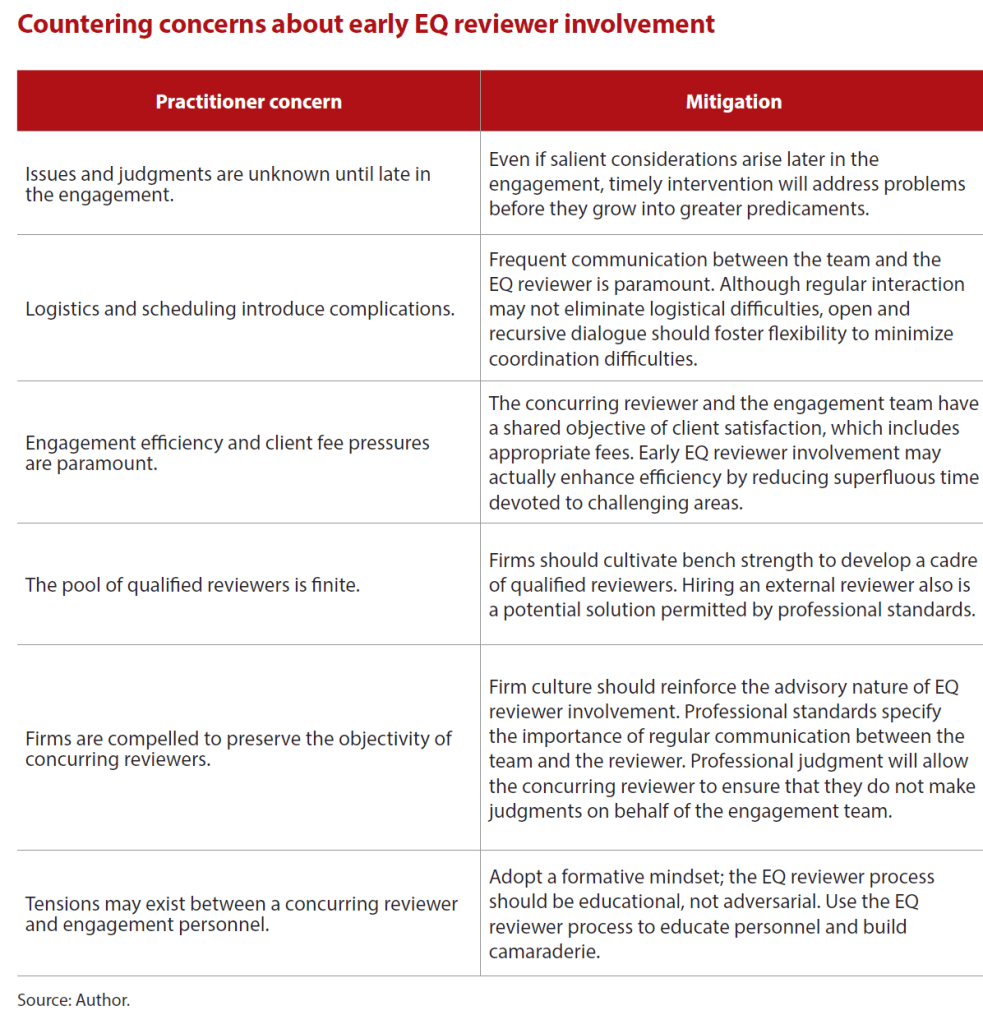

If early EQ reviewer involvement is a panacea, why don’t firms universally adopt this best practice? Practitioner reluctance falls into six broad themes. Some concerns are thornier than others, but progressive firms can use the following suggestions to address apprehension. (See the table, “Countering Concerns About Early EQ Reviewer Involvement,” below.)

WHEN COULD AN EARLY INVITATION BE APPROPRIATE?

A stitch in time saves nine. This proverb holds true for professional endeavors. Although late-stage EQ reviewer involvement may be acceptable for engagements with minimal quality risk, practitioners should strongly consider alternative timelines for complex, risky, and challenging situations. EQ reviewers may proactively offer advice and guidance if they do not make decisions on behalf of the team.

Let’s explore four real-world examples encountered by accountants in professional practice:

Acquisition bifurcation

This example involves the financial statement audit of a multilocation retailer with a quest for growth. During the year being audited, the client acquired a smaller retail chain via an asset purchase. The audit team discussed merger-and-acquisition activity during the planning meeting, performed risk assessment procedures, and conducted the audit.

The concurring review did not unearth deficient audit procedures or documentation. Rather, the financial statements were problematic.

Notable net assets acquired by the client included accounts receivable, inventory, property, equipment, furniture, and accounts payable. When preparing the statement of cash flows, the engagement team failed to recognize that year-to-year changes in accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable were not solely due to operational activities; they simply used each account’s increase to determine operating cash flows. However, a portion of the annual change was attributed to investing activities borne by the acquisition of the target company’s net assets. The engagement team scrambled to bifurcate the statement-of-cash-flows effects between the operating and investing sections, and the audit partner delivered the finished product at the 11th hour.

Taking things to the next level

An accounting firm historically performed review engagements for a manufacturer. However, the service level was recently elevated to an audit. Even though there is some overlap, an audit requires far more extensive evidence to support the reasonable assurance of an auditor’s opinion versus the limited assurance of an accountant’s review conclusion.

Ugly circumstances arose once the EQ reviewer observed that the engagement team did not perform substantive tests regarding the opening balances of accounts receivable and inventory in accordance with AU-C Section 510, Opening Balances — Initial Audit Engagements, Including Reaudit Engagements. Even if the engagement team could circle back to the client to request additional information to support relevant assertions, it would be impossible to accomplish this before the date specified in the client’s loan documents. Moreover, the inability to physically observe beginning inventory was particularly troublesome because time travel was not an option.

The firm ultimately determined that it obtained sufficient, appropriate evidence to opine on the ending balance sheet. However, the firm could not render an opinion regarding the income statement, statement of stockholders’ equity, and statement of cash flows. Scope limitations affected a substantial portion of these financial statements, creating a pervasive effect (AU-C Section 705.06) that would require a disclaimer of opinion (AU-C Section 705.20).

Early EQ reviewer involvement would have rendered a happier ending. Whenever an engagement transitions from one level of service to another, CPAs should amplify quality risk.

If the EQ reviewer had had more than a few days to offer advice, the engagement team might have crafted strategies to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence. Instead of spending a few early hours with the concurring reviewer, the engagement team faced the much more daunting task of preserving the client relationship in the aftermath of an engagement that went sideways.

Adjusting to the new normal

Implementation of new standards usually should compel early EQ reviewer involvement. Two fresh examples include the novel revenue recognition provisions of FASB ASC Topic 606, Revenue From Contracts With Customers, and the overhauled lease accounting guidance of ASC Topic 842, Leases. Given these standards’ widespread implications for a broad client base, savvy firms recognized the need for a common script and unified playbook.

Busy season is not the time to unpack a new accounting standard. Beyond jeopardizing efficiency, this is far too late to assess ramifications for clients’ financial reports. Moreover, a lack of harmony introduces the risk that numerous engagements will reach the EQ reviewer’s desk with problematic deficiencies. Standard setters intentionally offer lengthy implementation periods, especially for major pronouncements, because they realize that firms benefit from proactivity. Much like a quarterback coordinating a football team’s effort on the playing field, firms should encourage quality review personnel to proactively establish firmwide best practices to minimize surprises during the quality review process.

Navigating without a compass

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, P.L. 116-136, introduced unexpected recognition and presentation uncertainty because borrowers obtained Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funding in the form of traditional commercial loans with promised U.S. Small Business Administration forgiveness for borrowers that expended funds according to the act’s provisions. Practitioners espoused diverse views regarding derecognition of PPP liabilities. Some argued for removal once there was certainty regarding a borrower’s compliance with PPP provisions whereas many others advocated for a more conservative approach that would delay derecognition until forgiveness was granted.

Even FASB acknowledged that extant U.S. GAAP offered limited guidance; on Dec. 4, 2025, it published guidance on accounting for government grants. New Accounting Standards Update 2025-10, Government Grants (Topic 832): Accounting for Government Grants Received by Business Entities, applies to all business entities, except for not-for-profits and employee benefit plans, that receive a government grant.

We cannot predict the next situation that will create a professional thirst for formal guidance. However, given widespread developments such as artificial intelligence, cryptoassets, and environmental, social, and governance matters, we can be reasonably confident that practitioners will encounter such circumstances again. A well-researched, universal stance based upon proactive EQ reviewer involvement may be the best proxy for official guidance when standard setters leave professionals empty-handed.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

If you remember nothing else, please know that professional standards allow firms to customize EQ reviewer involvement if they implement safeguards to address the tension between EQ reviewer objectivity and engagement success. Perhaps this means you invite an EQ reviewer to the planning meeting. Or maybe you need recursive and dynamic discussions throughout various stages of the engagement. Fortunately, if you can ensure that the EQ reviewer does not assume engagement team functions, you probably can craft a solution that will prevent unexpected surprises.

Although partners and lead engagement professionals might expend additional effort during engagement planning, wouldn’t you prefer to invest a few hours conducting a pre-mortem brainstorming session to contemplate what might go wrong instead of squandering much more time to address a postmortem aftermath that could jeopardize your firm’s reputation or worse?

About the author

Christopher Harper, CPA, DBA, MBA, is an assistant professor of accounting with Grand Valley State University’s Seidman College of Business. He also serves as a senior manager and director of education for Hungerford CPAs + Advisors, a firm with five offices in West Michigan. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Jeff Drew at Jeff.Drew@aicpa-cima.com.

LEARNING RESOURCE

Advanced auditing and accounting topics will be on the agenda as the biggest event in the accounting profession celebrates its 10th anniversary at the ARIA in Las Vegas. Don’t miss it!

June 8–11

CONFERENCE

For more information or to make a purchase, go to aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.

MEMBER RESOURCES

Articles

“Common Audit Claims and Defenses,” JofA, Dec. 1, 2025

“Writing an Effective AI Prompt for an Audit,” JofA, Nov. 17, 2025

“QM Is Here: Advice From Early Adopters,” JofA, Nov. 1, 2025

“Lessons Learned From the First Year of SAS 145,” JofA, March 1, 2025

Tools

Peer Review Pilot Quality Management Checklists

Practice Aid, Establishing and Maintaining a System of Quality Management for a CPA Firm’s Accounting and Auditing Practice (2025 Update)

Practice Aid, The Monitoring and Remediation Process for a Firm’s System of Quality Management