- feature

- TAX

Transfer pricing: Not just for the tax department

Financial reporting needs to be given greater attention as the stakes of transfer pricing disputes rise.

Related

IRS should open Trump accounts for eligible children automatically, AICPA says

GAO says tax pros helped shape IRS response to ERC issues

Anticipated applicability date for future final RMD regs. announced

This article explores transfer pricing disputes with tax authorities and related disclosures in financial statements. Recent increases in companies’ risk exposure from these controversies have raised new concerns about properly reporting them as an uncertain tax position in financial statements.

Transfer pricing disputes between the IRS and well-known companies like Altera, Coca-Cola, Amgen, 3M, Medtronics, Caterpillar, Airbnb, and Facebook have received a lot of attention in the tax and business press. Recent increases in the amounts in dispute — some cases reaching tens of billions of dollars in proposed taxes, penalties, and interest — and greater IRS litigation success and penalties have triggered questions about reporting disputed transfer prices as an uncertain tax position.

WHAT IS TRANSFER PRICING?

The term “transfer price” refers to the internal price of transactions between divisions of the same company or related entities for goods, services, intangible property transfers, rents, and loans. A transfer price can have a significant effect on the consolidated group’s taxes because it determines the allocation of total income between the related entities.

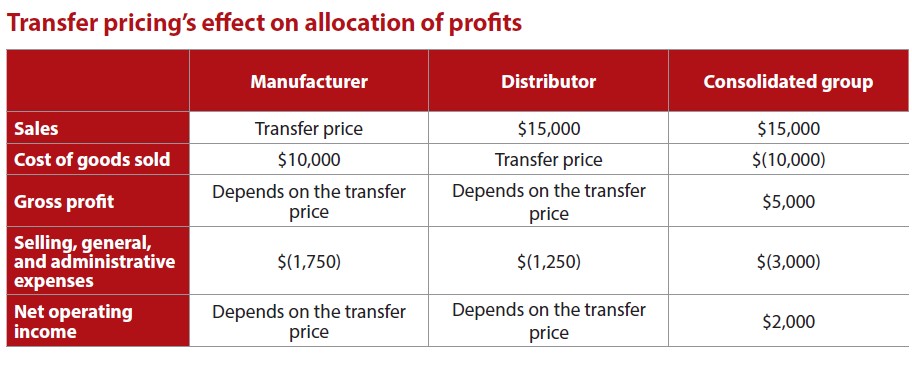

For an illustration of this, refer to the chart “Transfer Pricing’s Effect on Allocation of Profits,” which shows an allocation resulting when a manufacturer sells goods to an affiliated distributor at a transfer price.

Because the distributor’s sales of $15,000 are to unrelated end users, and the manufacturer’s cost of goods sold of $10,000 and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenditures as well as the distributor’s SG&A expenditures reflect payments to unrelated third parties, those items are market-based results. Thus, the price for the goods that the manufacturer sells to the distributor — the transfer price — will determine the allocation of net operating income between the related parties. The transfer price does not change the aggregate net operating income for the consolidated group, only its allocation between the related parties.

MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING ORIGINS

Early transfer pricing concepts were formulated for managerial accounting in the first part of the 20th century when companies began to vertically integrate and adopt decentralized multidivisional structures. Once an enterprise organized in a decentralized structure, a transfer price was necessary to price transactions between the related divisions or entities. That transfer price, not determined by market forces because both parties were under joint control, determined the allocation of profits or losses between the divisions or entities. The imposition of a transfer price allowed management to evaluate the performance of related divisions or entities.

The primary managerial accounting objective for transfer pricing is to “avoid suboptimization,” an efficiency objective to achieve the highest overall profit for the owners of the enterprise. A secondary transfer pricing objective is “fairness” to the head of each profit center. Specifically with respect to tax, the efficiency goal actively encourages manipulation of the transfer price to reduce global taxes paid by the multinational by shifting profits to the low-tax entity. Absent transfer pricing rules, multinationals could use transfer pricing to shift large amounts of income from one tax jurisdiction to another.

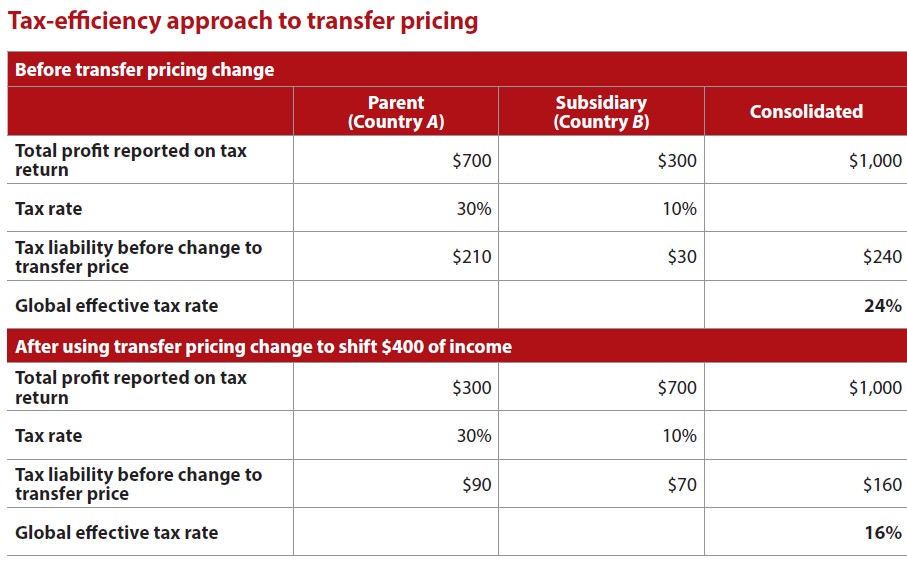

The chart “Tax-Efficiency Approach to Transfer Pricing” shows how a change in transfer price could shift profits from a high-tax jurisdiction to a low-tax jurisdiction, thus achieving a substantial reduction of the overall effective tax rate.

TRANSFER PRICING FOR TAX

Tax authorities are well aware of the motivation to use transfer pricing to achieve “tax efficiency.” Therefore, the United States and other countries have enacted strict transfer pricing rules and penalties and increased enforcement efforts to prevent multinationals from using transfer prices to artificially shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions. The goal of Sec. 482 is to ensure that taxpayers “clearly reflect income attributable to controlled transactions [i.e., transactions between related entities] and to prevent the avoidance of taxes with respect to such transactions” (Regs. Sec. 1.482-1(a)(1)). This goal is often measured by reference to the “arm’s-length standard,” the basis for all U.S. transfer pricing regulations since 1935. The regulations explain the arm’s-length principle as follows: “In determining the true taxable income of a controlled taxpayer, the standard to be applied in every case is that of a taxpayer dealing at arm’s length with an uncontrolled [i.e., unrelated] taxpayer” (Regs. Sec. Regs. Sec. 1.482-1(b)(1)).

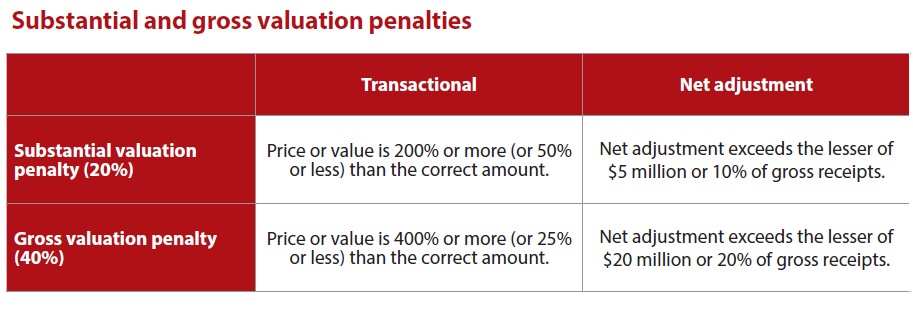

The Internal Revenue Code also contains transfer pricing—specific penalties to discourage noncompliance with Sec. 482. Secs. 6662(e) and (h) established penalties of 20% and 40%, respectively, for certain increases in U.S. corporate income tax attributable to Sec. 482 adjustments (the 40% penalty is available for all transfer pricing adjustments that exceed $20 million). See the chart “Substantial and Gross Valuation Penalties,” which shows that penalties can be assessed for exceeding certain transactional or net adjustment thresholds.

These penalties are not deductible. When determining penalties, adjustments are excluded from the net Sec. 482 adjustment calculation if the taxpayer can demonstrate with contemporaneous documentation that it determined its price using one of the transfer pricing methods enumerated in the Sec. 482 regulations in a reasonable manner (Sec. 6662(e) (3)(B)(i)). Although the transfer pricing regulations do not require contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation, documentation has become widespread because contemporaneous documentation can demonstrate the reasonableness of transfer pricing determinations, thereby avoiding transfer pricing penalties.

TRANSFER PRICING DISPUTES

For decades, the IRS compiled a poor record in transfer pricing litigation. However, in recent years, the IRS has achieved dramatic improvement in transfer pricing case outcomes, achieving at least a partial win in four recent transfer pricing cases. Further, the IRS has recently changed its policy to assert transfer pricing penalties more frequently.

Until five years ago, the last notable transfer pricing litigation win for the IRS was 40 years before, in DuPont in 1979 (E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 608 F.2d 445 (Ct. Cl. 1979)). Beginning in 2019, the IRS has had wins or partial wins in the following cases:

- Altera Corporation & Subsidiaries, 926 F.3d 1061 (9th Cir. 2019): On June 22, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the Ninth Circuit decision in favor of the IRS involving approximately an $81 million tax deficiency regarding the inclusion of stock-based compensation in the cost pools under a cost-sharing agreement.

- The Coca-Cola Company & Subsidiaries, 155 T.C. 145 (2020): On Nov. 18, 2020, the Tax Court entered its decision reflecting a tax deficiency of approximately $2.7 billion and applicable interest of approximately $3.3 billion.

- 3M Company & Subsidiaries, 160 T.C. No. 3 (2023): On Feb. 9, 2023, the Tax Court ruled in favor of the IRS in a case involving a $23.7 million adjustment for royalty payments limited under Brazilian domestic law.

- Medtronic, Inc., T.C. Memo. 2022-84: On Aug. 18, 2022, the Tax Court rejected the transfer pricing analysis of both the IRS and the taxpayer, applying an unspecified method to determine the royalty rate for license agreements between the taxpayer and its Puerto Rican subsidiary to arrive at a tax underpayment of $175 million.

Transfer pricing cases recently filed with, or still being litigated in, the Tax Court include:

- Amgen Inc. et al., T.C. No. 16017-21 (petition filed 7/26/21): Alleged tax deficiency of $3.6 billion for tax years 2010–2012; total alleged underpayment of $10.7 billion of tax and penalties for tax years 2010–2015. See also Roofers Local No. 149 Pension Fund v. Amgen Inc., No. 1:23-cv-02138 (S.D.N.Y. filed Mar. 13, 2023) (a related shareholder lawsuit).

- Newell Brands, Inc., T.C. No. 11897-24 (petition filed 7/19/24): Alleged underpayment of $90 million of tax and $34 million in related penalties for tax years 2011–2015.

- Airbnb Inc., T.C. No. 12423-24 (petition filed 7/30/24): Alleged underpayment of tax of $1.33 billion and $573 million in penalties for 2013.

The largest transfer pricing controversy has yet to reach Tax Court. Microsoft has disclosed that it is currently engaged in a long-standing transfer pricing dispute with the IRS over $28.9 billion of additional taxes, plus penalties and interest, allegedly owed for tax years 2004–2013.

In addition to improving its track record in litigation, the IRS has announced a more assertive approach to transfer pricing penalties. For the last four years, IRS officials have made a number of public statements regarding the Service’s intention to enforce transfer pricing penalties more vigorously. Consistent with these statements, the IRS is asserting penalties in four recent disputes — Amgen, Newell, Airbnb, and Microsoft. Whether the Service’s enforcement priorities in this area will change going forward remains to be seen.

FINANCIAL REPORTING OF TRANSFER PRICING

Since 2006, FASB has given detailed guidance about how companies should identify and report uncertain tax positions (UTPs) on the financial statements. First with FASB Interpretation No. 48, Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes — an Interpretation of FASB Statement No. 109 (FIN 48), and later with FASB Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 740, Income Taxes, FASB has dictated how to determine the minimum recognition threshold that must be achieved before a tax position is recognized in the financial statements.

All tax positions, including transfer pricing, are evaluated using a two-step process. The first step is recognition or nonrecognition of a tax position: “An entity shall initially recognize the financial statement effects of a tax position when it is more likely than not, based on the technical merits, that the position will be sustained upon examination” (ASC Paragraph 740-10-25-6).

The second step, applied only if the position has been recognized, is measurement of the tax benefit. “A tax position that meets the more-likely- than-not recognition threshold shall initially and subsequently be measured as the largest amount of tax benefit that is greater than 50 percent likely of being realized upon settlement with a taxing authority that has full knowledge of all relevant information” (ASC Paragraph 740-10-30-7).

The measurement of the amount of benefit to recognize considers both sides of the transactions and assumes that both tax authorities have full knowledge of all relevant information when calculating any associated tax reserve. The aggressiveness of foreign tax authorities, the selection of the best method for measurement purposes, the calculation of arm’s-length ranges, and the use of multiyear data should be considered from both sides when measuring the tax position. Detection risk is not a factor to be considered in determining whether a position is uncertain.

Measurement also includes interest on the difference between the tax position that should have been taken and the amount actually reported or intended to be reported on the tax return. Penalties imposed by the respective jurisdictions on the underpayment of tax should also be included and recorded in the period in which the tax position is taken (ASC Paragraph 740-10-25-57).

Disclosure of the interest and penalty classification policy is required in the footnotes of the financial statements (ASC Paragraph 740-10-50-19).

Because relatively few disputes are resolved through litigation, the measurement of the tax position is often based on management’s best judgment of the amount the taxpayer would ultimately accept in a settlement with taxing authorities. This approach has sometimes led to a lack of adequate disclosure for transfer pricing matters in financial statements. Even when transfer pricing disputes are identified in the financial statements, it is often extremely unclear how the associated tax reserves have been calculated.

Given the IRS’s previous poor track record in litigation and reluctance to assert penalties when documentation exists, companies willing to pursue tax litigation through the appeal process have often concluded that low or no reserve was necessary. The recent trend of IRS success in transfer pricing litigation and changed penalty position provides additional information for companies to consider when identifying, recognizing, and measuring the tax benefits that they ultimately expect to realize.

Questions have begun to emerge regarding the application of Topic 740 to transfer pricing matters. In 2023, the Roofers Local No. 149 Pension Fund sued Amgen Inc. and others alleging that Amgen failed to adequately disclose information about transfer pricing disputes with the IRS regarding the allocation of profits between Amgen affiliates in the United States and Puerto Rico. This shareholder lawsuit is currently being litigated in a federal district court in New York. According to the plaintiff, although Amgen had specific information in its possession about IRS proposed adjustments for years 2010–2012 and 2013–2015 before the July 29, 2020, filing of its quarterly report on SEC Form 10-Q, Amgen did not share that information in its 10-Q. Amgen did disclose the transfer pricing dispute with the IRS regarding the Puerto Rico transactions and take the position that the IRS positions were “without merit,” but it omitted the fact that the amount at issue was over $10.7 billion in total. Recent commentators have raised the question how a taxpayer could have a multibillion-dollar tax dispute on appeal yet have a reserve of less than $500 million (see, e.g., Rapoport, “Amgen, Coke Set Aside Only Fraction of Billions They May Owe IRS,” Daily Tax Report, Bloomberg Tax (Nov. 20, 2024)).

TRANSFER PRICING COMMANDS ATTENTION

Transfer pricing has been a top concern of tax executives for decades. The uncertainty surrounding the outcome, the cross-border nature, the size of the issue, and the penalty exposure have combined to command attention within the tax departments of multinationals. Now, recent increases in the size of transfer pricing disputes, the rising probability of IRS success, and the likelihood of penalties have raised new concerns about the reporting of transfer pricing disputes as UTPs in financial statements.

About the author

Steven C. Wrappe, J.D., LL.M., is a managing director with Grant Thornton Advisors LLC in Washington, D.C. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Paul Bonner at Paul.Bonner@aicpa-cima.com.

LEARNING RESOURCES

Learn to better understand transfer pricing and how important it is for decentralized entities that are organized as a group of divisions.

CPE SELF-STUDY

Income Tax Accounting — Tax Staff Essentials

This all-new course uses scenarios and examples to illustrate the complexities of accounting for income taxes.

CPE SELF-STUDY

For more information or to make a purchase, go to aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.

AICPA & CIMA MEMBER RESOURCES

Article

“Increased U.S. Transfer Pricing Enforcement: What’s at Stake?,” The Tax Adviser, Feb. 1, 2024

Tax Section resource

Podcast episode

“Global Tax Trends: What CPAs Need to Know Now,” AICPA Tax Section Odyssey, Sept. 5, 2024

The Tax Adviser and Tax Section

AICPA Tax Section members receive a subscription to The Tax Adviser digital issues in addition to access to a tax resource library, member-only newsletter, and four free webcasts. The Tax Section is leading tax forward with the latest news, tools, webcasts, client support, and more. Learn more here. The current issue of The Tax Adviser and many other resources are also available at thetaxadviser.com.