- feature

- TECHNOLOGY

A taxonomy for classifying digital assets

A nonauthoritative guide aids accountants with discussions about digital assets, general ledger account management, establishing internal controls, and complying with anticipated regulatory changes around reconciliations and disclosures.

Related

Differentiating agentic and generative AI — and more with a Tech Q&A author

How AI is transforming the audit — and what it means for CPAs

Promises of ‘fast and easy’ threaten SOC credibility

TOPICS

A nonauthoritative guide aids accountants with discussions about digital assets, general ledger account management, establishing internal controls, and complying with anticipated regulatory changes around reconciliations and disclosures.

Digital assets emerged 14 years ago with bitcoin, issued by an anonymous creator as a distributed form of digital value exchange requiring no trusted intermediary. Combining encryption techniques, some of which had been in use since the 1950s, the bitcoin creator developed a new type of asset also known as “crypto.” It rapidly caught on through the 2010s, and by the end of the decade the AICPA formed the Digital Assets Working Group to address questions about accounting for and auditing of digital assets.

Earlier this year, FASB issued an exposure draft related to specific types of cryptoassets (see Proposed Accounting Standard Update, Intangibles — Goodwill and Other — Crypto Assets (Subtopic 350-60): Accounting for and Disclosure of Crypto Assets). As digital assets become more prevalent, the need for CPAs to understand the types of these assets is more pressing. The taxonomy presented herein is suggested as a nonauthoritative classification system of digital assets for accounting purposes. The taxonomy supports standardized classifications and definitions to aid accountants with discussions about digital assets, general ledger account management, establishing internal controls, and complying with anticipated regulatory changes around reconciliations and disclosures. It is also useful for accounting professors who want to introduce digital assets to their students.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BLOCKCHAINS AND DIGITAL ASSETS

Digital assets exist on blockchains, which are distributed ledgers maintained by a network of participants, also known as nodes. Each node is typically a separate electronic device that is connected to a network that maintains a full or partial copy of a given blockchain and participates in the process to add new records to the ledger. The nodes compile incoming transactions into “blocks” and validate the transactions, operating through protocols that require a majority of nodes to agree that the blocks contain valid transactions. For example, attempting to send 10 bitcoin when the sender’s wallet only has two bitcoin would be rejected as an invalid transaction. Nodes have different functionality, and they may be configured in various ways. Some nodes are considered participating nodes and are incentivized to review and validate blocks through payments in the form of newly generated native cryptoassets from the protocols, or amounts collected as transaction fees from users of the blockchain. Node validation protects against double-spend and over-spend, as described above, but does not prevent theft or unauthorized transactions.

Every digital asset must exist on a distributed ledger such as a blockchain. Some have their own blockchains, but many are issued on preexisting blockchains. For example, most nonfungible tokens (NFTs) live on the Ethereum blockchain. The original asset of the Ethereum blockchain is ether (ETH).

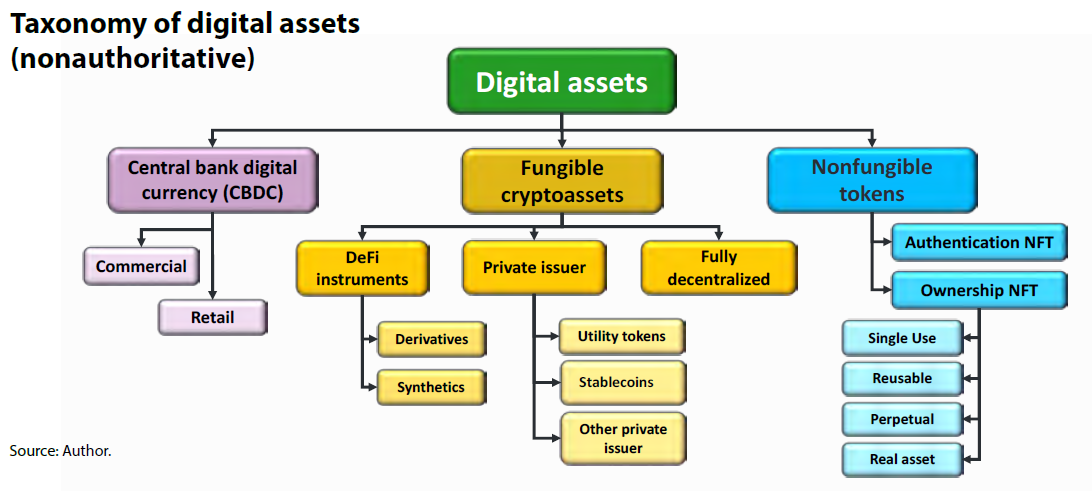

THE DIGITAL ASSET TAXONOMY

To identify the relevant properties of a given digital asset, I evaluated several factors including, but not limited to, fungibility, control and issuance, intended use, underlying assets, lifespan, and period of use (see the chart, “Taxonomy of Digital Assets (Nonauthoritative),” below). Further subdivisions exist in each category, but it is up to the reporting entity to determine the appropriate level of detail and segregation (see the sidebar, “NFTs, DAO Tokens, and Semi-fungible Tokens and Securities,” at the end of this article).

CENTRAL BANK DIGITAL CURRENCIES

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are a controversial digital asset that would be minted and controllable by a nation’s central bank. As of February 2023, 11 countries had launched CBDCs with more than 100 others, representing 95% of the world’s GDP, funding research into CBDC pilots and white papers.

The FedNow payment processing platform, a service the Federal Reserve launched in July 2023 to increase government control of citizen payments, does not appear to be implementing a CBDC.

There are two types of CBDCs: retail and commercial.

Retail CBDCs:

- Intended for citizens’ day-to-day use.

- Resemble fiat currency but are fully digital and not exchangeable to cash.

- Transactions are logged on a private blockchain visible to government officials.

- Vendor acceptance is controllable similar to other restricted benefit funds.

Commercial CBDCs:

- Issued and controlled by a central bank for settlements between member banks.

- Not for public use or distribution.

Public controversy over retail CBDCs derives from their controllable nature. Supporters highlight improved government transparency and the ability to control expenditures of federal grant, aid, and social program support distributed to states, entities, and individuals. For example, COVID-19 relief funds were used to buy personal luxury goods and cars. If those funds were distributed as a CBDC, the government could, in theory, prohibit them from use at luxury goods vendors. Unlike other digital assets, the blockchain ledgers of a retail CBDC would be controlled by central bank nodes and only visible to select government entities.

Currently, FASB’s project on cryptoassets does not apply to CBDCs. Should CBDCs become official currency, accounting guidance will have to address whether CBDC balances should be presented in the “digital assets” line item of the financial statements or as part of the cash balance.

FUNGIBLE CRYPTOASSETS

Each unit of a fungible cryptoasset has equal value to all other units of the same denomination. For example, one bitcoin is perpetually worth one bitcoin, regardless of exchange rates.

Fully decentralized

Generally, all fungible cryptoassets are issued by private developers or entities. In a select few cases, the developer is unknown or has little interaction with the asset’s smart contract and blockchain. Bitcoin is the foremost example of a fully decentralized cryptoasset. Distinguishing when a token is fully decentralized or issuer-controlled is important, as it informs risk assessment and internal controls.

Indicators of full decentralization may include:

- The developer is unknown or not involved in the network management.

- Changing the blockchain or the asset’s smart contract operation protocols requires a majority vote by a quorum of asset holders or node operators.

- Blockchain or smart contract protocols are managed through a distributed autonomous organization (DAO) with no entity exercising significant influence.

Private issuer

Developers often remain heavily involved in private-issuer coins. These projects tend to be still working to stand up to full functionality but can also be more mature blockchains with active management involvement. For example, the Ethereum Foundation took an active role in managing the migration of the Ethereum nodes network to a proof-of-stake validation protocol, which radically changed how the blockchain nodes operated, and remains involved in network operation.

Utility token: A utility token is issued for a specific purpose or platform, such as DAO tokens issued for voting on organizational decisions. DAOs are user-controlled organizations with elected or no central management that often make organizational decisions through voting. Voting rights are typically determined by the amount of DAO tokens a user owns.

Even though a utility token has a specific purpose, it may still be traded on centralized or decentralized exchanges. Ether (ETH) is one example of a utility token. The Ethereum blockchain was built as a platform to enable a multitude of applications, and the ETH coin is its utility token. ETH is the native token of the Ethereum Foundation and Ethereum blockchain. A native token refers to a token issued by an entity and used in its business operations. Native tokens have parallels to equity and, as such, are excluded for the issuer from FASB’s proposed crypto accounting standard scope.

Examples include:

- Native tokens used to settle transactions within an exchange, such as the centralized exchange Binance’s BNB tokens, decentralized exchange tokens like PancakeSwap’s CAKE, or decentralized finance (DeFi) platform Aave’s AAVE token. A native token has parallels to equity shares. FASB’s proposed accounting standard update excludes native tokens for the issuer from its scope for this reason. Holding a native token of an unrelated party remains in scope.

- DAO and other governance tokens designed for buying control or voting rights in a decentralized organization such as PlannerDAO’s PLAN or the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s APE coin issued by and used in the ApeCoin DAO.

Stablecoins: Stablecoins have two major subtypes: asset-backed tokens and algorithmic stablecoins. Asset-backed tokens may be single or multi-asset backed. Asset-backed, fiat-pegged tokens are generally designed to maintain a 1:1 exchange ratio to a fiat currency. USDT (Tether) and Gemini claim to have cash and cash equivalents on deposit at financial institutions equal to the circulating token supply.

An algorithmic token and tokens backed with “baskets” of multiple other cryptoassets maintain a 1:1 exchange ratio with pegged assets through an algorithm that adds (“mints”) and removes (“burns”) tokens from the circulating supply.

Algorithmic tokens have higher risk than fiat-backed tokens. The 2022 implosion of crypto markets began with the collapse of algorithmic stablecoin Terra (Luna). Terra was a stablecoin and Luna a DAO governance token tied to the Terra platform. In spring 2022, a “whale” (a user holding a large amount of the asset) sold $85 million of Terra, causing the algorithm to depeg from its 1:1 target with the U.S. dollar. This depeg, or “slip,” led to a mass sell-off. The algorithm was not able to adjust the coin supply fast enough, and the value of both Terra and Luna plummeted. Entities holding significant amounts of either coin saw their holdings evaporate, which set off a chain reaction of defaults and bankruptcies as capital evaporated from crypto markets.

Other private-issuer coins: This category is a catch-all for private-issue coins that do not meet other category definitions. As the crypto markets develop, assets in this bucket may emerge as distinct types.

DeFi instruments

Most DeFi products are private-issuer tokens of some kind. This category includes derivatives (futures and options) and synthetics, which are DeFi tokens created to represent pools of underlying assets that include stocks, commodities, or other financial assets. DeFi instruments are often generated and priced based on liquidity pools, which are financing protocols that allow users to deposit and “stake” crypto or financial assets like stock shares, similar to putting money in escrow, in order to borrow or trade into other assets.

Derivatives: Crypto derivatives include futures, swaps, options, and other financial derivatives built on pools of cryptoassets. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) regulates crypto derivatives but not the underlying coin. For example, the CFTC brought charges against Mango Markets, a crypto futures trading platform, for selling unregistered bitcoin futures, but the CFTC does not oversee or regulate bitcoin itself.

Synthetics: Synthetics are tokens typically pegged on a 1:1 basis to a stock, commodity (physical raw or natural products such as gold, silver, wheat, corn, and soy), or nonderivative financial asset or instrument. The purpose of synthetics is to make financial assets interchangeable with digital assets. The risk associated with a synthetic will often be determined by its underlying asset(s) and the stability of the DeFi protocol issuing it.

NONFUNGIBLE TOKENS

NFTs use cryptography to generate a unique ID or “token” representing a physical or digital object that is linked to an owner’s wallet address using a blockchain transaction. NFTs are like digital fingerprints that prove ownership of a digital or physical item.

Accounting for NFTs has yet to be addressed. One area that may require authoritative guidance is when a reporting entity preparing GAAP financials would be required to present NFTs in the “digital assets” line item on the face of financials or separately, and what type of disclosures are necessary.

Authentication NFTs

Authentication NFTs are created solely to support the validation of a digital ID, most commonly for tracking items in a supply chain. They either have no stand-alone market value and/or are valued in fiat currency with no associated cryptoasset valuation. The underlying technology may be described as blockchain or distributed ledger technology and is often a private and permissioned blockchain where all nodes are known entities, usually distributed internally in an organization or in a supply chain, unlike public blockchains where anyone can set up a node and download the blockchain ledger.

For example, Walmart’s blockchain supply chain built on IBM’s Hyperledger private chain is a well-known example of authentication NFTs. Each produce item receives its own barcode, and a digital twin is created on a blockchain ledger. At each point in the supply chain, scanning the barcode instantly updates the record.

Ownership NFTs

Ownership NFTs, and specifically reusable ownership NFTs, are the most common NFTs. Users pay crypto-denominated fees to create, buy, and sell these NFTs. They play a role in virtual worlds and gaming by demonstrating ownership of digital objects.

Single use: Single-use NFTs have limited use and little to no resale value, including NFTs that are burned after a specific use or for a period of time.

Examples are:

- Tickets that do not “transform” into a resellable collectible;

- Single-year memberships;

- Digital awards and badges with only sentimental value; and

- Gaming items usable in only one game or platform, with limited long-term reusability and little to no secondary market value.

Reusable: Reusables are the largest category of NFTs and include art, collectibles, avatars and profile pictures, digital fashion, and music. These NFTs have resale value, and buyers often purchase them to benefit from their value appreciation. For some reusables, age increases their value.

A royalty or creator fee is nearly always included with a reusable NFT. (These fees are also attached to perpetual and real asset NFTs.) Reusable NFTs may come with a physical component, such as a digital artwork that has a physical twin, or an avatar that comes with perks such as access to membersonly websites or real locations, access to exclusive merchandise and in-person events, or access to events held in a digital world (a “metaverse”). The physical components and other perks may or may not be transferable upon resale.

Examples include:

- Profile picture collections such as the Bored Ape Yacht Club, CryptoKitties, and CryptoPunks, used as a person’s avatar on those and other websites.

- Private club memberships (either virtual, inperson, or both) accessed by owning an NFT.

- NFT tickets that transform into resellable memorabilia after the event.

- Gaming items usable across platforms and/or with a useful life exceeding one year.

- Album art that also unlocks access to download or stream other content.

Perpetuals: Perpetuals are NFTs that represent a digital location, such as an internet domain name or a “land” plot in a virtual world, sometimes referred to broadly as “the metaverse.” It is already possible to obtain mortgages and loans with the virtual land plot as collateral. These NFTs are unlikely to change hands often and are often longterm investments.

Real asset: Real asset NFTs represent a physical real asset on a blockchain. Unlike an authentication NFT, a real asset NFT will be denominated in a fungible cryptoasset and listed on an NFT market. The tokenization of real assets is typically for the purpose of:

- Simplifying ownership transfers and reducing fees.

- Fractionalizing ownership across a group.

- Crowdfunding the purchase or management of real assets, especially when the assets are owned or operated through a DAO.

NFTs, DAO tokens, and semi-fungible tokens and securities

Unusual coins that may have confusing names include nonfungible tokens (NFTs), distributed autonomous organization (DAO) tokens, and semifungible collections. Each type fits into the taxonomy.

DAO tokens and NFTs

Some fungible digital assets are called NFTs, which are typically fungible, private-issuer utility tokens that may provide voting rights or access to use services from a specific platform. When used for DAO governance, these tokens can be likened to shares of voting stock.

Semi-fungible tokens

Semi-fungible tokens are often game items with hundreds of identical copies. Digital playing card decks for tabletop games are a prime example. Some of these cards will be considered rare and have a high resale value for decades. But most cards have a low value and are not used more than a few months. The low-value cards may be designated as single-use NFTs, while the high-value ones may qualify as reusable NFTs, especially if a card is retained for the purpose of realizing appreciated market value.

Securities

Securities can exist in many of the categories of this taxonomy. Designation as a security is a legal question that may or may not affect the accounting for the asset.

Special thanks to friends and colleagues who reviewed, debated, and challenged this taxonomy with me including the Government Blockchain Association, CryptoCFOs community, Peter Rehm, and the AICPA technical reviewers.

About the author

Stacey Ferris, CPA, CFE, is a forensic accountant and associate director at HKA, a UK-based global expert consulting firm, and an adjunct professor of accounting with the University of Maryland Robert H. Smith School of Business in College Park, Md., teaching blockchain and digital assets in the master of accountancy program.

LEARNING RESOURCES

Learn specific considerations for auditing digital assets, including client acceptance and continuance; risk assessment processes and controls; and laws, regulations, and related parties.

CPE SELF-STUDY

Accounting for Digital Assets Under U.S. GAAP

Understand how to explain bitcoin payments to clients and how to account for other transactions and investments involving crypto and digital assets under U.S. GAAP.

CPE SELF-STUDY

Accounting for Digital Assets under U.S. GAAP – Part II

Learn how to apply the AICPA Digital Assets Working Group’s practice aid to help account for digital assets.

CPE SELF-STUDY

For more information or to make a purchase, go to aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call the Institute at 888-777-7077.

AICPA RESOURCES

Articles

“What CPAs Need to Know About NFTs,” JofA, Oct. 2022

“Tackling NFTs in the Accounting Classroom,” JofA, Aug. 10, 2022

“Tackling the IT Challenges of Dealing With Cryptoassets,” JofA, July 2022

Podcast episode

“Digital Assets in Danger: How to Guard Against Hackers,” JofA, Feb. 3, 2023