- feature

- PERSONAL FINANCIAL PLANNING

Helping clients after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis

Related

How to ease taxes on inherited IRAs

Cost-of-living increases could hurt 2026 financial goals, poll says

Tax-efficient drawdown strategies in retirement

During the summer of 2022, Mark showed up at his financial planner’s office for an unscheduled visit. He told the receptionist he was there to pay his cellphone bill. Unfamiliar with Mark, the receptionist told him the firm could not take his check. Confused, he left. The following week he showed up again, asking to pay his cellphone bill. A new receptionist, also unfamiliar with Mark, explained that the firm could not take his check. Again, he left quietly. Neither receptionist told anyone else at the firm about the incidents.

CPAs can provide value to a client with a recent Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Studies show that proactive management of the disease can improve the quality of life of the affected client and their care partner, and CPAs, of course, are particularly adept at planning. But working with a client with Alzheimer’s requires specific skills, including an understanding of the disease and its progression.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. Roughly 1 in 9 Americans age 65 and older has Alzheimer’s dementia, according to a 2023 Alzheimer’s Association report. As the U.S. population ages, the problem is likely to grow because the percentage of people who have Alzheimer’s dementia increases with age: Currently, 5.0% of people age 65 to 74, 13.1% of people age 75 to 84, and 33.3% of people age 85 and older have Alzheimer’s dementia. People under age 65 can develop the disease, too. In addition, the Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the United States has 11.5 million family members and other caregivers providing unpaid care to people with Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

Beyond the demographics, Alzheimer’s is often ranked in polls as the disease most feared — even more than cancer and heart disease. Many people have known someone who suffered from the disease and watched as they gradually lost their autonomy and their knowledge of themselves.

Why is the issue of Alzheimer’s disease so important to CPA financial planners? Recent studies demonstrate that the ability to handle financial tasks competently is one of the first cognitive skills to deteriorate. And these skills may begin to decline as much as six years before a formal diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

CPAs CAN BE PART OF A COMMUNITY OF CARE

Knowing the warning signs of Alzheimer’s and other dementias is important in serving clients. In some cases, the client’s behavior will indicate that there are cognitive problems, as in the story that opened this article about a client named Mark. Even subtle behavioral changes are important. Often, it is the care partner who sees the symptoms first while the individual with the disease remains in denial.

While the CPA financial planner is in no position to diagnose a disease in a client, having a clear understanding of what steps to take when concerns arise is important.

Despite the current limitations on accurate early diagnosis, a good financial planner still considers the possibility of a future diagnosis. This is especially true if the client’s family has a history of the disease. The cost of Alzheimer’s — especially the cost of caregiving Medicare doesn’t cover — is large and cannot be ignored. Information on what Medicare does cover can be found on the Alzheimer’s Association website.

THE ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE CONTINUUM AND FINANCIAL PLANNING

A dementia-informed firm must regularly communicate with clients and educate them about Alzheimer’s. A valuable source of information is the Alzheimer’s Association’s Education Center. Staff and advisers should be trained on the topic as well.

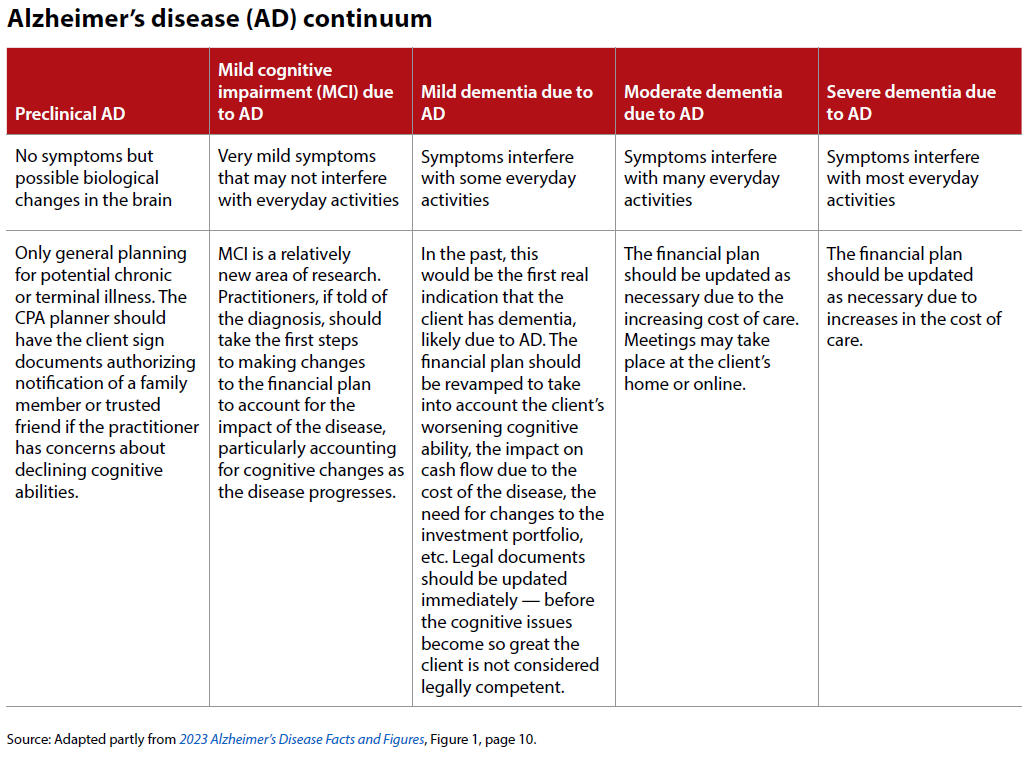

Alzheimer’s disease is best described as a continuum of five stages:

- Preclinical Alzheimer’s;

- Mild cognitive impairment;

- Mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s;

- Moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s; and

- Severe dementia due to Alzheimer’s.

Each stage has different financial planning implications, which are described in the table “Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Continuum,” below.

The Alzheimer’s stages are not equal in duration. Their lengths also vary by individual.

Two of the stages are relatively new to the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. One is the preclinical stage, which is included because biomarkers that may detect the presence of the disease are understood to be present 20 or more years before the symptoms appear. The preclinical phase also may involve subjective cognitive decline, which refers to a person’s own perception that their thinking abilities or memory are worsening. You may have clients who occasionally complain about their thinking abilities as they age, or you might encounter a family member with similar complaints about the client’s abilities. It is important not to dismiss those concerns out of hand and, instead, discuss the issue.

The term “mild cognitive impairment,” the second stage of the Alzheimer’s disease continuum, has gained broader use by doctors since about 1999 to identify individuals presenting the earliest detectable symptoms of dementia. Before the recent advances in research, a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s was not possible without any symptoms.

Understanding the Alzheimer’s disease continuum is important because CPA financial planners naturally assume that their clients have the cognitive ability to process and understand financial planning information. If that assumption is wrong, adequate communication between the planner and the client may not be possible. Educating clients about the Alzheimer’s disease continuum will strengthen the client/planner relationship and increase the likelihood of a successful engagement.

ADJUSTING A BROKEN FINANCIAL PLAN

Once a diagnosis of the suspected cause of the symptoms is made, and is determined to be Alzheimer’s disease, the financial plan must be adjusted to include the costs of future care needs and other expenses. In cases where the person with Alzheimer’s or the care partner had been working for an income, adjustments to future income projections will be necessary. Many care partners must reduce their work hours or leave outside employment altogether to fulfill their caregiving duties.

A careful analysis of the income statement and balance sheet is necessary to determine the optimal funding source for the care expenses. The tax implications of any asset liquidation to pay for care expenses must be considered. The client must begin careful tracking of deductible health care expenses. Careful tax planning for large expenses, such as payments for custodial care at a nursing home, is important as the disease progresses.

Adjustments to the client’s investment portfolio may be necessary because of changing risk tolerance and/or to increase cash flow to meet anticipated care expenses or make up for the loss of income. Legal documents must be updated. A review of Medicare or other health care coverage is necessary to determine if the optimal coverage is in place given the new diagnosis. For example, the coverage provided by a Medicare supplement plan compared to a Medicare Advantage plan is important to ensure the person with Alzheimer’s has access to their preferred doctors and health care facilities. Quality of care should not be sacrificed for lower costs.

Strategies to pay the anticipated costs might include self-funding or using long-term-care insurance (if the client has it) or some combination of both. The reality, however, is that few families can afford the cost of care for any length of time. That is why the unpaid care provided by family members is one of the largest sources of “funding,” along with federal, state, and local government assistance.

Medicaid is often the last resort as the client depletes all their other available assets to pay for care. Many individuals living with the disease became dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare is a federal program that provides health care benefits based on the person’s age (65 or older) or meeting certain disability requirements before age 65. Medicaid, a program supported by the federal and state governments, offers aid based on the person’s financial need, regardless of age or disability status.

Many veterans diagnosed with Alzheimer’s are eligible for Veterans Affairs benefits to assist with the cost of care.

The practitioner should recommend that the family meet to discuss the client’s care plan (prior to this, the practitioner should ask the client(s) to sign a letter identifying who the CPA planner may contact if concerns arise regarding the client’s ability to communicate or cognitive issues.). This may also include seeking information from the health care professionals and social workers involved. Incorporating the relevant portions of the care plan will help the planner create a more accurate household budget. Through care planning, individuals and their caregivers can learn about various treatments (medical and nonmedical), services offered in the community, and other information that can improve the Alzheimer’s patient’s quality of life.

A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease often causes anxiety as the individual and his or her family face an uncertain future. In addition, Alzheimer’s disease itself can cause a person increased anxiety due to biological changes in the brain. The CPA can help reduce the stress for the individual diagnosed and the family by creating a budget centered around the prognosis and the care plan (see the sidebar “Mark’s Story: A Case Study” at the end of this article).

A POST-DIAGNOSIS FINANCIAL PLAN IS NEEDED

The new financial plan should include the following financial statements:

The care budget: This is a household income/ cash flow statement estimating the impact of Alzheimer’s on income and expenses. Because it is difficult to predict the disease’s progression, the care budget typically projects no more than 12 to 18 months. Care expenses should include input from health care professionals and other families familiar with the care needs of a family member with dementia. A support group can be a tremendous source of information; families can find local support groups through the Alzheimer’s Association. If there is a monthly cash flow deficit, liquidation of a portion of the family’s assets may need to be considered. This is where the care balance sheet is useful.

The care balance sheet: This statement summarizes all household assets that, if necessary, may be used to pay for care expenses. This includes, for example, access to home value through the sale of the home (downsizing), a reverse mortgage, or a line of credit. Assets may need to be repositioned to help meet other financial needs than originally intended. For instance, an advance death benefit available through a life insurance policy can be tapped, even though this is probably not why the policy was purchased. But the high cost of care may warrant making changes. Unfortunately, the client often must pick the best choice from a list of poor alternatives.

(For an in-depth discussion of how to create a care budget and a care balance sheet, see the author’s earlier article “Advising Chronically or Terminally Ill Clients,” JofA, Aug. 2018.)

BE A DEMENTIA-INFORMED FIRM

A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia presents unique financial challenges to your clients. To help clients, a dementia-informed firm must offer accessible, positive, and stigma-free services. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are not easy to talk about with family members and friends, let alone a CPA financial planner. Laying the groundwork for such discussions begins well before the actual diagnosis. Let clients and prospective clients know that your firm is dementia-friendly, is knowledgeable about the disease, and demonstrates those skills every day.

Mark’s story: A case study

In November, Mark and his wife, Linda, showed up at their financial planner’s office for a scheduled visit to discuss their Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage. The planner, Paul, anticipated a 30-minute meeting. The receptionist recognized Mark from his visit in July. She took Paul aside before the meeting started and mentioned that Mark had been at the office while Paul was on vacation, asking to pay his cellphone bill.

In the meeting, Paul learned that Mark had been diagnosed recently with Alzheimer’s dementia. The 30-minute meeting turned into a two-hour session on the impact of the diagnosis on Mark and Linda’s financial plan.

The first thing Linda noticed was Mark’s losing track of their finances. For over 30 years, Mark did the budgeting and made most of the investment decisions based on Paul’s recommendations. In the past, Mark paid all the bills on time. Now, bills had often been missed and were piling up on Mark’s desk at home or found discarded in the trash.

While Paul usually prided himself on his knowledge of Alzheimer’s and its impact on a client’s financial plan, he blamed himself for not training his staff on the warning signs of dementia. If they had told Paul about Mark’s strange visits, he would have taken immediate action — in this case, contacting Linda. Paul believed that for his firm to be considered “dementia-informed,” regular staff training on the disease was key.

When Mark and Linda first became his clients, Paul asked them to sign a document identifying a person he could call if he had concerns about either’s cognitive abilities. In this case, they named each other and their adult son who lived nearby. The document alleviated Paul’s concerns regarding client confidentiality. (For additional information on client confidentiality, see “AICPA’s Revised Confidentiality Rule and Sec. 7216,” JofA, March 2015.)

In prior meetings, Paul had discussed and projected the cost of a chronic or terminal illness. Neither Mark nor Linda was covered by a long-term-care insurance policy. They had set aside a portion of their assets to pay for potential costs. In the meeting, Paul explained that Mark and Linda would need to revise their financial plan because of Mark’s condition. The three discussed what the initial steps in this process would be.

About the author

James Sullivan is the president of Paying for Alzheimer’s in Wheaton, Ill. He is a CPA (retired) and holds a master’s degree in accounting science from the University of Illinois at Urbana. He is a volunteer community educator for the Alzheimer’s Association. Sullivan lost his older brother, Rick, to Alzheimer’s disease and an older sister, Kathy, to Binswanger’s disease, a rare form of vascular dementia. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact joaed@aicpa.org.

AICPA RESOURCES

Articles

“How to Guard Client Finances Against Dementia,” JofA, Jan. 2020

“Advising Chronically or Terminally Ill Clients,” JofA, Aug. 2018

“Cognitive Impairment Does Not Necessarily Have to Derail Your Clients’ Planning,” JofA, June 12, 2017

Podcast episodes

“The Intersection of Money and Memory,” AICPA PFP Section, Feb. 17, 2022

“Guiding Your Clients Who Are Financial Caregivers,” AICPA PFP Section, Jan. 19, 2022

“Guiding Clients With Diminishing Mental Capacity,” AICPA PFP Section, Sept. 9, 2021

“The Financial Impact of Alzheimer’s Disease,” AICPA PFP Section, July 17, 2020

For PFP Section members

The Adviser’s Guide to Retirement and Elder Planning: Healthcare Coverage Planning, 6th edition

The Adviser’s Guide to Financial and Estate Planning, Vol. 3, 12th edition, Chapters 26 and 33

PFP member section and PFS credential

Membership in the Personal Financial Planning (PFP) Section provides access to specialized resources in the area of personal financial planning, including complimentary access to Broadridge Advisor. Visit the PFP Center. Members with a specialization in personal financial planning may be interested in applying for the Personal Financial Specialist (PFS) credential.