- feature

- TAX

Understanding the new kiddie tax

Find out how the taxation of children’s unearned income was changed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2018. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

IRS should open Trump accounts for eligible children automatically, AICPA says

GAO says tax pros helped shape IRS response to ERC issues

Anticipated applicability date for future final RMD regs. announced

TOPICS

Many areas of the U.S. individual income tax were changed for tax years 2018 through 2025 when P.L. 115-97, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), was enacted in late 2017. One of those areas was the “kiddie tax,” the tax imposed on certain children with unearned income. Congressional efforts to amend the Internal Revenue Code garnered substantial press coverage from late 2017 through early 2018 given the significant and far-ranging changes made to the tax law as a whole. Major changes were made to the kiddie tax as well, yet press coverage of these changes has been scant.

Since the TCJA became law, a few articles have reported that the kiddie tax is calculated simply by reference to the estate and trust tax rate table. This synopsis of law changes may have been inspired by page 9 of the congressional conference committee report for P.L. 115-97, which stated, “taxable income attributable to earned income is taxed according to an unmarried taxpayer’s brackets and rates. Taxable income attributable to net unearned income is taxed according to the brackets applicable to trusts and estates” (H.R. Conf. Rep’t No. 115-466, 115th Cong., 1st Sess. 197 (Dec. 15, 2017), available at docs.house.gov. Yet this description of how the kiddie tax is computed is not entirely accurate. The purpose of this article is to provide a robust discussion of the changes to the law to help practitioners better understand how the law has changed and to assist them in calculating estimated quarterly tax payments for children subject to the tax.

HOW THE TCJA SIMPLIFIED THE KIDDIE TAX

The AICPA advocated for a simpler kiddie tax as Congress crafted the TCJA. This advocacy was at least partially successful, since some of the complexities in the old kiddie tax are no longer present in the new law. The previous law required the kiddie tax to be the greater of two tax calculations. The first calculation was the tax on the child’s taxable income as if the kiddie tax did not exist. The second calculation was the sum of the tax on the child’s net unearned income assessed at a parent’s marginal tax rate plus the tax computed on the remaining taxable income at the child’s tax rates. This second calculation introduced complexity because the child’s taxable income had to be bifurcated to compute tax using both marginal tax rates — the parent’s and the child’s.

The old law was also complex when the child’s parents were divorced or married filing separately, because the tax preparer had to determine which parent’s marginal tax rate should be used. Another complexity stemmed from computing the child’s allocable share of the parental tax when the child had siblings who were also subject to the kiddie tax.

Finally, under the old law, it was difficult to calculate the kiddie tax when the parent(s) had a different tax year than the child. Thanks to changes made by the TCJA, all of the foregoing complexities vanish for 2018 through 2025, since none of these provisions apply to the calculation of the kiddie tax during this time frame. The conference committee report for the TCJA confirms Congress’s intent was to simplify the calculation of the kiddie tax so that a child’s tax is “unaffected by the tax situation of the child’s parent or the unearned income of any siblings” (H.R. Conf. Rep’t No. 115-466, 115th Cong., 1st Sess. 197 (Dec. 15, 2017)).

ONE CONVENIENCE LOST

Unfortunately, an administrative convenience in the old kiddie tax did not find its way into the new rules. Under the old law, parents could elect to report a child’s unearned income on their income tax return using Form 8814, Parents’ Election to Report Child’s Interest and Dividends. Parents whose children had only interest and dividends subject to the kiddie tax could avoid the added cost and hassle of filing income tax returns for the children. It appears this convenience does not exist in the new law since there is no corollary provision, nor does the new law expressly reference the election provision in the old law. While the removal of this administrative convenience will be irksome for some taxpayers, it is a logical change to the law since the kiddie tax is no longer calculated at the parents’ rates.

NEW COMPLEXITIES IN COMPUTING THE KIDDIE TAX

Sec. 1(g) contained the rules for computing the kiddie tax before the recent law changes. Sec. 1(j) was added to the law to provide all the individual tax rate changes enacted by the TCJA. Sec. 1(j)(4) presents the new kiddie tax rules, which are a mix of old and new elements.

Elements of the old kiddie tax that still apply

The determination of who is subject to the kiddie tax remains the same, so children who would have been subject to the old kiddie tax are subject to the new kiddie tax. A child’s taxable income is also calculated the same way it was under the old kiddie tax rules: gross income less allowable deductions.

Even though children subject to the kiddie tax are permitted to itemize their deductions, virtually all of these children claim the standard deduction, according to historical IRS data. The law allows a dependent child to claim the single standard deduction, but Sec. 63(c)(5)(A) limits the deduction for 2018 to the greater of $1,050 or the sum of the child’s earned income plus $350. Therefore, a dependent child’s standard deduction could be as small as $1,050 or as large as $12,000, the amount of the basic standard deduction for single taxpayers in 2018.

The new law retains the computation of “net unearned income” (NUI) as a key element in determining the new kiddie tax. NUI is the excess of a child’s unearned income over the sum of (1) $1,050, plus (2) the greater of $1,050 or the child’s itemized deductions related to the unearned income. By law, NUI cannot exceed the child’s taxable income.

Earned income continues to be defined as the sum of amounts received as compensation for personal services as well as taxable distributions from qualified disability trusts. In contrast, a child’s unearned income will generally comprise income generated by property, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains, along with certain nonproperty income, such as taxable Social Security benefits and taxable scholarships.

Elements added to the kiddie tax

Despite Congress’s intent to simplify the kiddie tax, the TCJA introduced new elements that make its computation more complex. First, the law introduced the concept of “earned taxable income” (ETI). While ETI relates only to the computation of the kiddie tax, it has the potential to create confusion in at least two ways. First, the term “earned taxable income” is very similar to the term “earned income” (discussed above with respect to NUI), but these items are computed in distinctly different ways. ETI is taxable income less NUI, while earned income is the total of all the child’s compensation received for services provided during the year and taxable distributions to the child from a qualified disability trust.

ETI is also a misnomer for children whose only income for the year was unearned income. Despite having no income earned from their labor, these children will still have ETI because it is computed as the difference between the children’s taxable income and NUI amounts.

Another complexity introduced by the TCJA is that the kiddie tax must be computed using single tax rate tables, which have been modified by reference to the estate/trust tax rate tables. These modifications limit the amount of ordinary income taxed in each of the single income tax brackets based on the sums of a child’s ETI and specific income tax bracket amounts cross-referenced from the estate and trust income tax rate table.

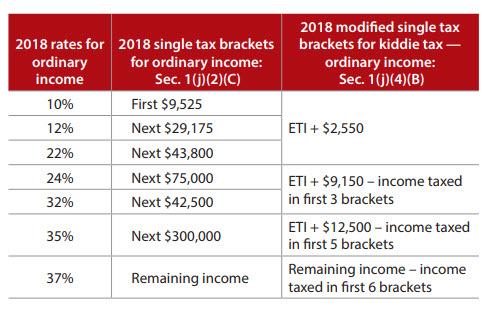

For 2018, a child’s income that can be taxed at rates below 24% is limited to the sum of ETI plus $2,550, the minimum taxable income for the 24% estate/trust tax bracket. Further, income that can be taxed at rates below 35% is limited to the sum of ETI plus $9,150, the minimum taxable income for the 35% estate/trust tax bracket. Income that can be taxed at rates below 37% is limited to the sum of ETI plus $12,500, the minimum taxable income for the 37% estate/trust tax bracket. Any remaining income that does not fit within the foregoing limits will be taxed at a rate of 37%. These tax bracket modifications are illustrated in the table “Modified Income Tax Brackets.”

Modified income tax brackets

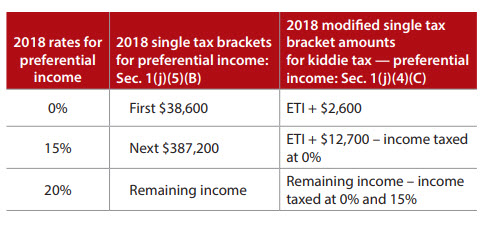

Similarly, the new kiddie tax rules modify the 0%/15%/20% breakpoints that would otherwise apply to a child’s net long-term capital gains and/or qualified dividends. These modifications are also computed as the sum of a child’s ETI and specific 0%/15%/20% preferential rate breakpoints borrowed from estates and trusts.

The 0% tax rate applies to a child’s preferential income up to the sum of ETI plus $2,600, the new 0%/15% breakpoint created for estates and trusts. The 15% tax rate applies to preferential income up to the sum of ETI plus $12,700, the new 15%/20% breakpoint created for estates and trusts. Preferential income in excess of the sum of ETI plus $12,700 will be taxed at 20%. These modifications are described in the table “Taxation of Child’s Preferential Income.”

Taxation of child’s preferential income

The foregoing tax rate modifications for both the ordinary and preferential tax rates are unique to each taxpayer since they are based on each child’s personal ETI for the year, adding another layer of complexity to the new kiddie tax calculations.

Overall effect of the rate modifications

The tax rate modifications cross-referenced from the estate/trust income tax rates can have the effect of shifting a child’s income into higher tax brackets before all the lower brackets are full, as well as removing certain tax brackets from the computation of the kiddie tax altogether. Furthermore, referring to the estate/trust income tax rates is a significant policy shift from the old rules, which taxed a portion of the child’s income at a parent’s tax rate. The congressional committee reports are silent about the reason for this shift.

HOW TO COMPUTE THE KIDDIE TAX

In preparation for the 2019 filing season, the IRS will update Form 8615, Tax for Certain Children Who Have Unearned Income, and IRS Publication 929, Tax Rules for Children and Dependents, to facilitate computing the kiddie tax for the 2018 tax year. Software companies will update their tax return preparation products to incorporate the new law. In the meantime, this article demonstrates how to compute the new kiddie tax for one taxpayer. Additional examples can be found here, including examples of how the tax owed for children subject to the kiddie tax can change from 2017 to 2018.

EXAMPLE

A, who is 14 years old, has both ordinary income and income that is taxed at preferential rates. She was fortunate to be born into a family with the financial means to provide her with significant income-generating property. A owns U.S. obligations that pay $10,000 of interest annually. She also holds stock that pays qualified dividends of $35,000 annually. In addition to her portfolio income, A earns $5,000 from baby-sitting jobs throughout the year.

A’s filing status is “single,” and she must pay federal income tax on both her earned and unearned income annually. None of these funds are used for her support, so she is considered her parents’ dependent and is subject to the kiddie tax. Finally, while A may be required to pay state income taxes on some of her federal taxable income, this example assumes her state taxes are less than her standard deduction, so she will not itemize deductions. Further, the computation of her state tax liability will depend on her state of residency and, therefore, is beyond the scope of this article.

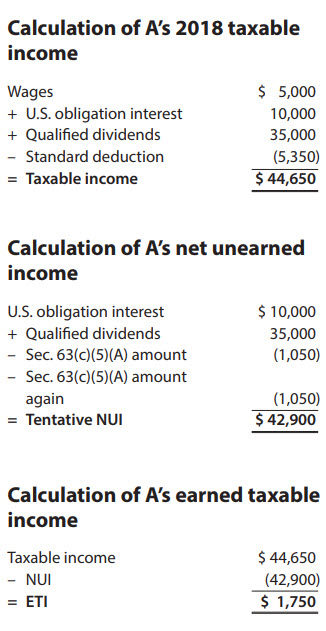

The first step in computing the kiddie tax is not unlike the first step in computing any tax — compute the tax base. Based on the foregoing information, A’s 2018 taxable income is shown in the table “Calculation of A’s 2018 Taxable Income.”

A’s NUI is computed as shown in the table “Calculation of A’s Net Unearned Income.” Because A’s tentative NUI of $42,900 is less than A’s taxable income of $44,650, NUI is $42,900.

A’s earned taxable income is computed as shown in the table “Calculation of A’s Earned Taxable Income.”

Since A has income that is subject to tax at both ordinary and preferential tax rates, taxable income must be bifurcated so that the appropriate tax rates can be applied. A’s ordinary taxable income equals $9,650, her $44,650 taxable income reduced by $35,000 of qualified dividends.

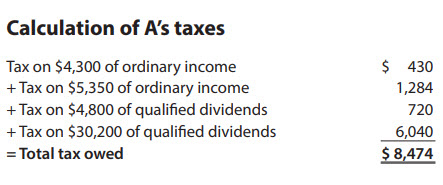

Tax on A’s $9,650 of ordinary taxable income is computed using a modified single tax rate table. The maximum taxable income that can be taxed at single rates below 24% is $4,300, the sum of $1,750 ETI plus $2,550. A will owe tax of $430 on this $4,300 since the entire amount fits within the 10% single tax bracket amount of $9,525. Further, A’s ordinary taxable income will not be taxed at the lower 12% and 22% single tax brackets because the law forces her remaining ordinary income of $5,350 into the 24% tax bracket.

The maximum amount of A’s taxable income that can be taxed at single rates below 35% is $10,900, the sum of $1,750 ETI plus $9,150. However, since her ordinary income is only $9,650, the amount of income that is taxed in the 24% tax bracket is the difference between $9,650 and the $4,300 that was already taxed in the 10% bracket. A will owe tax of $1,284 on this $5,350 since the entire amount fits within the 24% single tax bracket amount of $75,000. Tax owed on A’s ordinary income is summarized in the table “Taxation of A’s Ordinary Income.”

Taxation of A’s ordinary income

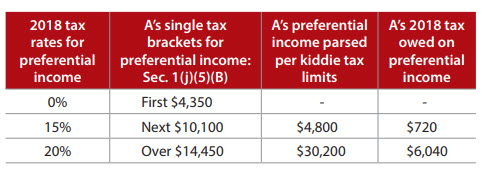

Tax on A’s $35,000 of qualified dividends is computed using the 0%/15%/20% preferential tax rate breakpoints, which are modified with reference to her ETI. None of these dividends are eligible for taxation at 0% because that rate applies to preferential income up to $4,350 (her $1,750 ETI plus $2,600), and her ordinary income of $9,650 surpasses that threshold. The 15% rate applies to $4,800 of these dividends because that rate applies to preferential income up to $14,450 for A (her $1,750 ETI plus $12,700), and only the difference of $4,800 between this cap of $14,450 and ordinary income of $9,650 is eligible to be taxed at 15%. The remaining dividends of $30,200 are taxed at 20% because they exceed the $14,450 threshold computed above. A’s tax owed on qualified dividends is summarized in the table “Taxation of A’s Qualified Dividends.”

Taxation of A’s qualified dividends

KIDDIE TAX SIMPLIFICATION?

When most of the TCJA’s provisions took effect on Jan. 1, 2018, many Americans hoped they would see simplified income tax calculations and reduced tax liabilities over the next eight years. While many complexities of the old kiddie tax were eliminated, new complexities were introduced. Further, whether the new law results in tax savings or additional tax due is different for each child. It cannot be taken for granted that a taxpayer’s kiddie tax liability for 2018 will be similar to what it was in 2017. Detailed calculations showing the difference in the kiddie tax liability under old law and new law can be found here.

About the authors

Kate Mantzke, CPA, Ph.D., is the Donna R. Kieso Professor of Accountancy. Brad Cripe, CPA, Ph.D., is the assistant department chair, the Gaylen and Joanne Larson Professor of Accountancy, and director of Graduate Studies. Suzanne Youngberg, CPA, MST, is an instructor and the MST adviser in the Department of Accountancy. They are all faculty members in the Department of Accountancy at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, Ill.

To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Sally P. Schreiber, a JofA senior editor, at Sally.Schreiber@aicpa-cima.com or 919-402-4828.

AICPA resources

Articles

- “Counterintuitive Tax Planning: Increasing Taxable Scholarship Income to Reduce Taxes,” The Tax Adviser, May 2018

- “Tax Practice & Procedures: Kiddie Tax May Be Due on College Scholarships,” The Tax Adviser, April 2016

- “Financing for College With the Uniform Transfers toMinors Act,” JofA, July 2015

- “The Dreaded Kiddie Tax,” JofA, July 2007

CPE self-study

- Cut Your Client’s Tax Bill: Individual Planning Tips and Strategies (#732194, text)

For more information or to make a purchase, go to aicpastore.com or call the Institute at 888-777-7077.

The Tax Adviser and Tax Section

Subscribe to the award-winning magazine The Tax Adviser. AICPA Tax Section members receive a subscription in addition to access to a tax resource library, member-only newsletter, and four free webcasts. The Tax Section is leading tax forward with the latest news, tools, webcasts, client support, and more. Learn more at aicpastore.com/taxsection. The current issue of The Tax Adviser and many other resources are available at thetaxadviser.com.