- feature

- TAX

What to do with math error notice letters from the IRS

The best advice if you or a client receives one is not to ignore it.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2018. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

IRS issues higher 2026 depreciation limits for passenger automobiles

New Schedule 1-A for tips, OT, car loans, and senior deductions published

Senate bill targets preparers who break the law, expands IRS reforms

TOPICS

In 2015, the IRS received more than 146 million individual tax returns and audited 1.2 million of them, a mere 0.8% (IRS 2016). At the same time, the IRS found more than 2.17 million math errors from individual tax returns and sent more than 1.67 million math error notice letters (some returns have more than one error). What are these math errors, and how should taxpayers and tax practitioners respond to them?

MATH ERROR PROGRAM

The IRS uses several programs to check the accuracy of a tax return, and one of these programs is the math error program (Sec. 6213(b)). In this program, the IRS uses computers to screen all tax returns when processing them. When the IRS identifies math or clerical errors (collectively referred to as math errors) in a return, it will recalculate taxes, assess any interest and penalties, and send the taxpayer a letter detailing the math error. It is worth noting that the math error program uses computers to (1) screen all tax returns, and (2) send out notice letters without much human assistance. Different from the IRS audit process, the math error program, especially with the advancement of computer technology, is highly automated and has become an important tool for tax enforcement.

Congress first authorized the math error program in 1926, allowing the IRS to recalculate taxes due to obvious arithmetic errors on tax returns. Since then, Congress has expanded the program to include clerical errors and other math errors in addition to obvious arithmetic errors. The expansion came at the IRS’s request, since a regular audit notice was much costlier to the IRS than a math error notice. It is worth noting that detecting math errors is within the capability of computers. If an issue requires subjective judgment, such as underreporting income, the IRS will likely issue an audit notice instead of a math error notice. The sidebar “What Is a Math Error?” lists all the types of math errors with examples. As shown, a “math error” extends beyond making a mistake in adding or subtracting numbers.

DOES A MATH ERROR MEAN A TAXPAYER OWES MORE TAXES?

The good news is that a math error notice does not necessarily mean a bigger tax bill. The bad news is that additional tax liability can be high if a notice is unfavorable. A favorable adjustment occurs when a math error notice increases a taxpayer’s refund or decreases his or her balance due. An unfavorable adjustment occurs when a math error notice decreases a taxpayer’s refund or increases his or her balance due.

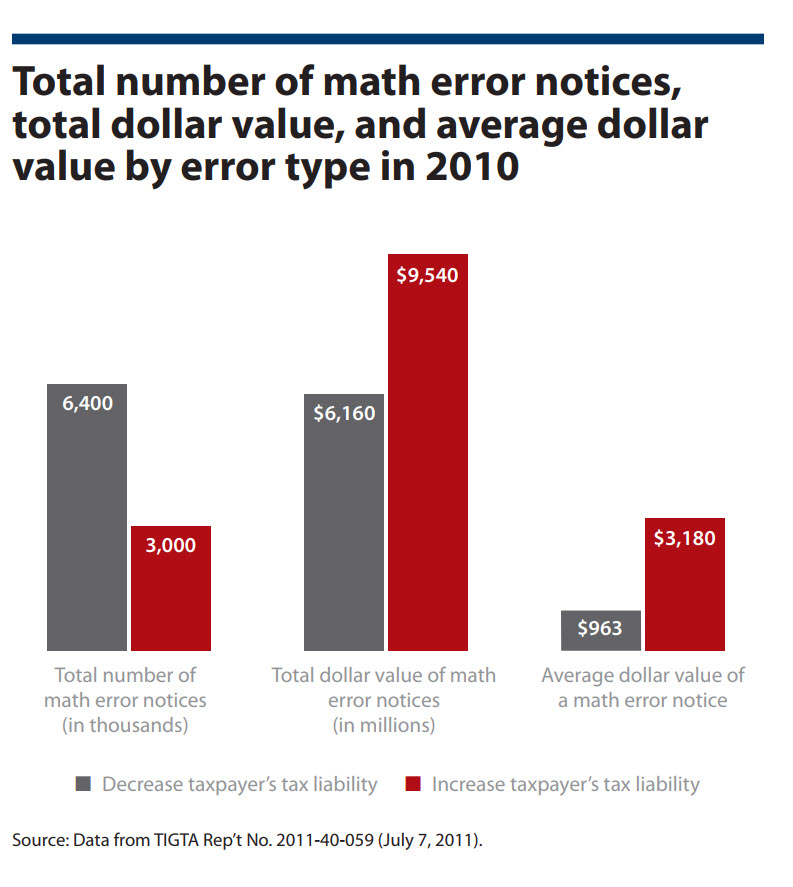

In 2010, the IRS issued more than 6.4 million favorable notices and more than 3 million unfavorable ones (Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) Rep’t No. 2011-40-059). Overall, only 31% of math error notices required taxpayers to pay more taxes. As shown in the chart “Total Number of Math Error Notices, Total Dollar Value, and Average Dollar Value by Error Type in 2010,” the Treasury lost nearly $6.2 billion of tax revenue from favorable math error notices but received an additional $9.5 billion of tax revenue from unfavorable notices. The chart also shows the average dollar value of favorable and unfavorable math error notices. On average, the Treasury lost $963 when issuing a favorable notice but received an additional $3,180 when issuing an unfavorable notice.

A TAXPAYER’S LEGAL RIGHTS ON RECEIVING A MATH ERROR NOTICE

A math error notice differs significantly from a regular audit notice in terms of legal rights. When the IRS issues an audit notice, it first sends a report letter to the taxpayer and includes items that need to be adjusted in terms of tax liability. The taxpayer has 30 days to either accept the adjustment or request an appeal. If the taxpayer does not respond to the initial letter, or if the appeal does not go through, the IRS will send a statutory notice of deficiency to the taxpayer, who has 90 days to respond to the notice.

To protect taxpayer rights, the government requires the IRS to inform the taxpayer of the right for petition or dispute. The government also prohibits the IRS from assessing and collecting additional tax on the return during those 90 days. If the taxpayer files a Tax Court petition in response to the notice, the IRS must wait until the final court decision before assessing additional taxes (Sec. 6212(c)(1)).

In contrast, a taxpayer has only 60 days to respond to a math error notice, which includes any additional tax assessment and penalties (Sec. 6213(b)(2)(A)). The IRS has to explain these errors and can start collecting the additional assessment only when the taxpayer agrees with the notice or after 60 days (Sec. 6213(b)(2)(B)). If a taxpayer disagrees with the assessment, he or she can request the IRS to abate it. However, the IRS does not have to inform the taxpayer of the right to abate, and, as a result, some math error notices do not explain this abatement right (“Math Error Notice Rights,” by Robert B. Nadler, The LITP Newsletter, p. 1 (December 2002)).

When a taxpayer requests an abatement, the IRS will use the deficiency procedures similar to those used in an audit. More importantly, a taxpayer cannot challenge the math error notice in the Tax Court until he or she requests the abatement. The Tax Court is the only judicial forum in which the taxpayer does not need to prepay the tax assessment. Taxpayers who receive math error notices may not have the extra cash to pay the assessment first. Therefore, it is important for tax practitioners to advise their clients to request an abatement if necessary.

WHAT TO DO NEXT AFTER RECEIVING A NOTICE

The decision about whether to appeal a math error notice depends on the accuracy of the notice and specific facts associated with it. If the assessment presented on the notice is correct, then there is no need to appeal. However, if the assessment is incorrect or if the taxpayer can reduce the assessment by providing additional documentation, the taxpayer should file for an abatement within 60 days, which will stop IRS tax collection (Sec. 6213(b)(2)). Requests for abatement are treated as protests. If the taxpayer does not file for an abatement within 60 days, he or she can still challenge the assessment during a Collection Due Process hearing (Internal Revenue Manual (IRM) §21.5.4, General Math Error Procedures).

If a taxpayer files an abatement, he or she needs to follow up and contact the IRS to see if the abatement has been processed. Although IRS employees are well-trained, it is impossible for them to know the intricacies of every math error. Therefore, it may be up to taxpayers or tax advisers to direct IRS employees to the relevant Code sections or portions of the IRM. The taxpayer should file the request using certified or registered mail instead of over the phone, for recordkeeping purposes.

If the taxpayer agrees with an unfavorable notice, he or she accepts a smaller refund or pays additional taxes. This includes cases when taxpayers do not respond to the notice. If the taxpayer disagrees with the notice, he or she must provide additional documents or information to the IRS to overturn it. Once the IRS receives that information, it will treat the response as either a substantiated response or an unsubstantiated response.

If the IRS agrees with the taxpayer based on the additional information, it treats the response as a substantiated response and reverses the math error adjustment. The taxpayer, therefore, does not have to pay additional taxes. If the IRS deems the additional supporting documents sent by the taxpayer inadequate, it will treat the response as an unsubstantiated response. In this case, the IRS generally reverses the math error adjustments and places an examination freeze on the taxpayer’s account, resulting in the tax return’s being referred to the Examination function for further review.

According to a 2011 report by TIGTA, 97% of taxpayer responses are substantiated responses (TIGTA Rep’t No. 2011-40-059). As long as a taxpayer or the tax adviser can provide adequate documents to support his or her disagreement with the initial math error notice, it is almost certain that the math error notice can be reversed. For example, if a taxpayer does not include the correct TIN in the original return, the IRS may reduce any tax credit that depends on this TIN. The taxpayer can provide the correct TIN in the appeal and then have the unfavorable notice reversed.

HOW TO PREVENT MATH ERRORS: COMMON MISTAKES

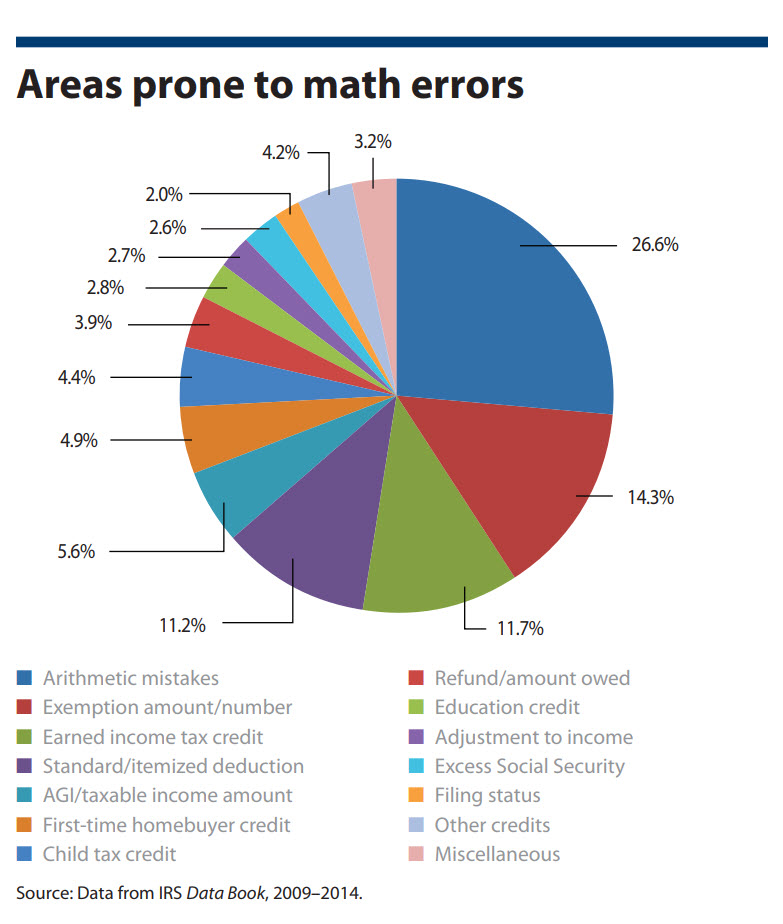

The IRS publishes data books every year and lists areas that are prone to math errors in the individual income tax return filings. The chart “Areas Prone to Math Errors” breaks down the areas in which math errors occurred from 2009 to 2014.

ADVICE FOR PRACTITIONERS

Math errors extend well beyond arithmetic and include several types of errors, and a number of errors occur quite frequently. Fortunately for taxpayers, most can be cleared up without further damage beyond the inconvenience. Still, the inconvenience is not insignificant and is often avoidable with either a practitioner’s assistance or just by using off-the-shelf tax preparation software, which cuts down on math errors.

As shown previously, the average amounts of favorable and unfavorable notices are strikingly different, however. And, as psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky note, “[L]osses loom larger than gains” (“Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, 42-1 Econometrica 263 (1979)). That is, a loss will generally be felt with more intensity than a gain of similar size.

Given the stress for taxpayers, tax advisers should therefore do their best to help clients avoid unpleasant surprises. First, tax advisers should inform clients that math error notices are not audits and that the IRS screens all tax returns for these errors. Second, tax advisers should respond promptly to a notice. When a taxpayer receives a notice, he or she may assume it is the tax adviser who made the mistake. However, the error could be from incorrect information the taxpayer provided, such as an incorrect TIN. Some math error notices are due to missing, incomplete, or incorrect information from taxpayers. When the relevant information is provided, most math error notices can be reversed.

The tax adviser should therefore carefully understand the math error notice and double-check TINs on the return where the error was noted. When requesting an abatement for a client, a tax adviser should provide all the necessary supporting documents and direct the IRS to the relevant sections of the IRM. Finally, not only should tax advisers understand what constitutes a math error, but they should also be aware of areas prone to math errors, such as exemptions and the earned income tax credit, so as to prevent their clients from making those errors in the first place.

What is a math error?

Under Sec. 6213(g)(2), math errors include:

- An error due to addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division.

- An incorrect use or selection of information from tax tables and schedules.

Example: A taxpayer who files as a head of household uses the married-filing-jointly table to calculate taxes.

- A transcription error in the same form or from another form.

Example: A taxpayer enters a salary amount that is inconsistent with that on his or her Form W-2, Wage and Tax Statement.

- An omission of required supporting forms.

Example: A taxpayer does not include Form 8863, Education Credits (American Opportunity and Lifetime Learning Credits), when claiming the American opportunity tax credit.

- Claiming credits or deductions that exceed statutory limits.

Example: The tuition and fees deduction a taxpayer claimed exceeds the limit allowed based on his or her modified adjusted gross income.

- Missing or incorrect taxpayer identification number (TIN) used for personal and dependency exemptions, child and dependent care credit, earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit, and education credits.

Example: A taxpayer claims his son as a dependent but does not include his son’s TIN or includes an incorrect one, making the claim invalid.

- Claiming an EITC based on self-employment income without paying self-employment tax.

- An EITC claim by a taxpayer who does not have a qualifying child and does not meet the age requirements (taxpayers must be between 25 and 64 to claim the EITC).

- Claiming a credit that is incorrect because of an age limit.

Example: A taxpayer claims the child tax credit for a dependent who is over 16.

About the authors

Russell Zhaochu Li (zhaochu@umflint.edu) is an assistant professor of accounting, and Clement Chen (clementc@umflint.edu) is a professor of accounting, both at the University of Michigan—Flint. Keith Jones (kjones5@una.edu) is a professor of accounting at the University of North Alabama in Florence, Ala.

To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Sally P. Schreiber, senior editor, at Sally.Schreiber@aicpa-cima.com or 919-402-4828.

AICPA resources

Article

“TIGTA: IRS Does Not Timely Resolve Math Error Disputes,” Aug. 24, 2011

The Tax Adviser and Tax Section

The Tax Adviser is available at a reduced subscription price to members of the Tax Section, which provides tools, technologies, and peer interaction to CPAs with tax practices. More than 23,000 CPAs are Tax Section members. The Section keeps members up to date on tax legislative and regulatory developments. Visit the Tax Center at aicpa.org/interestareas/tax.html. The current issue of The Tax Adviser and many other resources are available at thetaxadviser.com.