- feature

- TAX

Exploring the estate tax: Part 1

Practitioners should know these basics about estate taxes to better advise clients.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2017. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

IRS seeks to scrap basis‑shifting TOI reporting regulations

IRS Dirty Dozen adds new capital gains scheme for 2026

IRS proposal eases provision of 1099-DA statements by digital asset brokers

This is the first installment of a two-part article on the federal estate tax. Part 1 discusses the unified federal estate and gift tax rules, the exemption amount, the definition of a gross estate, gifts made within three years of death, estate valuation, and portability. The second part, to appear in the November JofA, covers estate tax planning techniques, including maximizing the marital deduction and the use of various types of trusts.

OVERRIDING GOAL: TAX MINIMIZATION

A major area of personal financial planning is planning for the transfer of property during an individual’s lifetime and at death. Although most individuals do not have enough money to be concerned about federal gift and estate taxes, minimizing gift taxes and estate taxes is a primary financial goal for many millionaires and billionaires.

The federal estate and gift tax is referred to as a unified tax because both taxes use the same tax rate schedule and the same credit against the tax, called the unified credit. The unified credit amount in 2017 is $2,141,800, which is the tax on $5,490,000 of taxable value (the calculations in this article are based on 2017 figures). This $5,490,000 is called the basic exclusion amount.

An individual will be liable for the gift tax only if during the individual’s lifetime he or she transfers property by gift in excess of the basic exclusion amount. Because the basic exclusion amount applies to both the gift and estate tax, an individual’s estate will be liable for the estate tax only when the taxable value of the estate exceeds the individual’s exclusion amount, less the amount of taxable gifts the individual made during his or her lifetime.

The federal estate tax is owed by only about 1 out of 700 estates. It has gone through many changes since 2001 when estates with a taxable value of more than $675,000 were liable for the estate tax. This amount was increased gradually from $1 million in 2002—2003 to $5 million in 2010—2011. After 2011, the $5 million basic exclusion amount is adjusted for inflation; for 2017, it is $5.49 million.

This article discusses the mechanics of the estate tax as well as a number of planning techniques to minimize the federal estate tax so that the estate can transfer the maximum value to its beneficiaries. Although this discussion focuses on the federal estate tax and does not review state estate taxes, the relevant state rules must also be addressed as part of an individual’s financial plan.

Under Sec. 2001(a), the estate tax is imposed on the transfer of the taxable estate of every decedent who is either a citizen or a resident of the United States. The estate tax is calculated by adding together the decedent’s taxable estate (the gross estate less allowable deductions) and the decedent’s adjusted taxable gifts to determine the estate tax base (see below).

Formulas for calculating estate tax base and net estate tax liability

Gross estate – deductions = Taxable estate

Taxable estate + adjusted taxable gifts after 1976 = Estate tax base

Tentative estate tax – gift taxes paid after 1976 = Gross estate tax

Gross estate tax – unified credit – other credits = Net estate tax liability

Adjusted taxable gifts are taxable gifts made by the decedent after Dec. 31, 1976, other than gifts that are includible in the gross estate of the decedent. Next, the estate tax rates are applied to the estate tax base amount to determine the tentative estate tax. Gift taxes paid by the decedent after 1976 are then deducted from the tentative estate tax to arrive at the gross estate tax. Finally, the decedent’s remaining unified credit and any other credits are deducted from the gross estate tax to determine the decedent’s net estate tax liability.

Estates use Form 706, United States Estate (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return, to calculate the estate tax liability of a decedent (this article does not address generation-skipping transfer (GST) taxes). Estates with a gross estate, plus adjusted taxable gifts, of more than the exclusion amount for the decedent’s year of death, and estates of any size whose executor elects to make a portability election, need to file an estate tax return, which is due within nine months after the date of the decedent’s death.

GROSS ESTATE

The gross estate includes all property, real or personal, tangible or intangible, wherever situated (Sec. 2031(a)). An estate lists property included in the gross estate on Form 706, Part 5, “Recapitulation,” lines 1—10.

LIFE INSURANCE

The gross estate includes the proceeds of life insurance in two situations (Sec. 2042):

- When the proceeds of life insurance are received by the estate as the beneficiary on a life insurance policy where the decedent is the insured; or

- When the proceeds of life insurance are received by beneficiaries other than the estate on a life insurance policy where the decedent is the insured and possessed at the date of death any of the incidents of ownership.

Incidents of ownership include the right to change the beneficiary, the right to transfer ownership of the life insurance policy, and the right to use the policy’s value as collateral for a loan. An incident of ownership also includes a reversionary interest (whether arising under the policy or other instrument or by operation of law), but only if the reversionary interest’s value exceeded 5% of the policy’s value immediately before the decedent’s death (Sec. 2042(2)).

The gross estate also includes the replacement value of a life insurance policy owned by the decedent where someone other than the decedent is the insured.

GIFTS MADE WITHIN 3 YEARS OF DEATH

The gross estate includes any interest in property (by trust or otherwise) transferred by the decedent during the three-year period ending on the date of the decedent’s death if the property would have been included in the decedent’s estate under Secs. 2036, 2037, 2038, or 2042 if it had not been transferred (Sec. 2035(a)). In addition, any gift tax paid on these gifts is included in the gross estate (Sec. 2035(b)).

GROSS ESTATE VALUATION

All property included in the gross estate is valued as of the date of the decedent’s death unless the executor elects the alternate valuation under Sec. 2032. If the executor elects the alternate valuation, the gross estate is valued as follows:

- For property distributed, sold, exchanged, or otherwise disposed of within six months after the decedent’s death, that property is valued as of the date of distribution, sale, exchange, or other distribution.

- Other property is valued as of the date six months after the decedent’s death.

The executor can elect the alternate valuation only if the gross estate and the sum of the estate tax on the estate and the GST tax on property included in the estate are less using the alternate valuation than the date-of-death valuation. The alternate valuation is calculated based on the aggregate value of the gross estate, not on an item-by-item basis. As a result, it is possible to use the alternate valuation even though one or more properties appreciate during the six-month period between the date of death and the alternate valuation date.

The basis of property received by an estate’s beneficiary is either stepped-up (if the property has appreciated) or stepped-down (if the property has depreciated) to the fair market value (FMV) of the property at the date of the decedent’s death or, if elected, the value at the alternate valuation date (Sec. 1014). As a result, any pre-death (or pre-alternate valuation date) appreciation of property will escape income taxes. Consequently, as a general rule, highly appreciated property should not be sold before death. On the other hand, any pre-death (or pre-alternate valuation date) decrease in the value of property will not be available as a potential loss deduction to the beneficiary of the property. Thus, as a general rule, if possible, property that has lost value should be sold before death so that the decedent can realize the loss and potentially take an income tax deduction for it.

DEDUCTIONS

Estate tax deductions are reported on Form 706, Part 5, “Recapitulation,” lines 14—23. Deductions include:

- Funeral expenses;

- Expenses incurred in administering property subject to claims;

- Debts of the decedent;

- Mortgages and liens;

- Net losses during settlement of the estate;

- Expenses incurred in administering property not subject to claims;

- Amounts passing to a surviving spouse; and

- Charitable, public, and similar gifts and bequests.

Commissions paid to the estate’s executor are allowed as a deduction on the estate tax return. Likewise, attorneys’ fees and accounting fees paid are allowed as a deduction. In valuing the gross estate, the executor often needs an appraiser’s services, and the appraisal fees are allowed as a deduction. All debts the decedent owed as of the date of death are allowed as a deduction, including mortgages, automobile loans, student loan debt, and credit card debt.

As noted above, the estate can take a deduction for losses incurred during the estate settlement, including losses arising from fires, storms, shipwrecks, or other casualties or from theft (Sec. 2054). In a recent Tax Court case, the court showed a willingness to interpret the language in Sec. 2054 broadly to allow an estate a theft loss deduction where a limited liability company owned by the decedent lost money in a Ponzi scheme, diminishing its value to the estate (Estate of Heller, 147 T.C. No. 11 (2016)).

Since the estate can take a deduction for the decedent’s debts, any medical expenses owed at death can be deducted on the estate tax return. Medical expenses owed at death, in the alternative, could be deducted on the decedent’s final income tax return if the estate pays the medical expenses within one year of death (Sec. 213(c), Regs. Sec. 1.213-1(d)). The deduction on the estate return would more likely than not be more beneficial than taking the medical deduction on the decedent’s final income tax return because of the adjusted gross income limitation on the deductibility of medical expenses, which does not apply to estate tax returns. The executor has the flexibility of claiming all or part of the medical expenses owed at death on the decedent’s final income tax return rather than on the estate tax return.

MARITAL DEDUCTION

In calculating the estate tax, married individuals are at a significant advantage over unmarried individuals since the estate of a decedent who was married at the time of death can take an unlimited estate tax deduction for all amounts passing to the surviving spouse (Sec. 2056(a)). Many married people have wills providing that all property passes to the surviving spouse. As a result, there is often no estate tax liability on the estate of the first spouse to die.

TAXABLE ESTATE, ESTATE TAX BASE, AND TENTATIVE ESTATE TAX

The taxable estate is the gross estate minus deductions. The estate tax is calculated on the estate tax base, which is the taxable estate plus adjusted taxable gifts after 1976. Once the estate tax base is known, the next step in the computation of the estate tax is to calculate a tentative estate tax on the estate tax base. Sec. 2001(c) contains the rate schedule that is used to calculate the tentative tax.

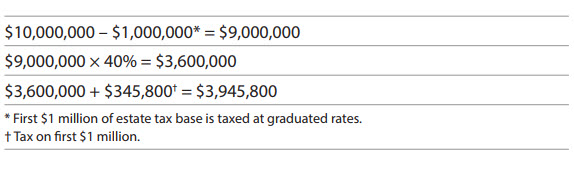

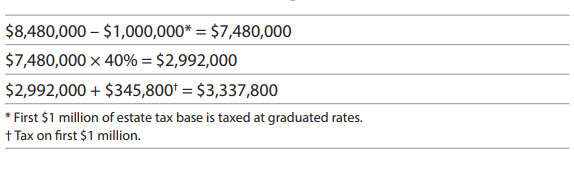

Example 1

An individual’s estate has an estate tax base of $10,000,000. The tentative estate tax is $3,945,800, calculated as shown in the table “Calculation of Tentative Estate Tax,” below.

Calculation of tentative estate tax

The gross estate tax, which is the estate tax before credits, is calculated by taking the tentative estate tax less gift taxes paid (after 1976) (Sec. 2001(b)). In Example 1, assume that the decedent didn’t pay any gift taxes after 1976. The gross estate tax would be $3,945,800. The unified credit and other credits would then be subtracted from the gross estate tax to determine the net estate tax liability.

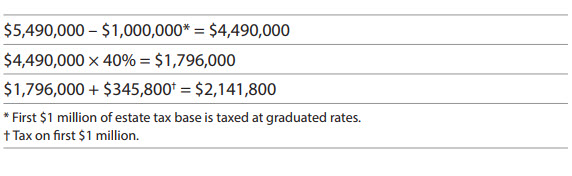

The unified credit is the estate tax on the applicable exclusion amount of $5,490,000.

For 2017, the unified credit is $2,141,800, computed as shown in the table “Computation of Unified Credit.”

Computation of unified credit

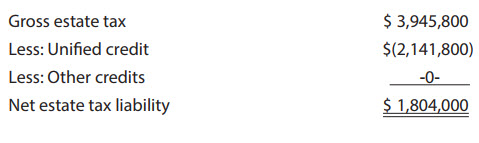

Assuming there are no credits other than the unified credit, the estate would have a net estate tax liability of $1,804,000, calculated as shown in the table “Calculation of Net Estate Tax Liability.”

Calculation of net estate tax liability

Other credits allowed against the gross estate tax include a credit for foreign death taxes and a credit for taxes paid on prior transfers, which are relatively uncommon.

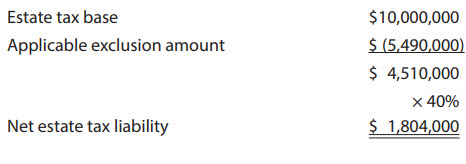

If the estate’s exclusion amount is more than $1 million, a more practical way to calculate an estate’s net tax liability is by subtracting the applicable exclusion amount from the estate tax base and then multiplying that amount by the highest marginal estate tax rate of 40%. Using the facts of Example 1, the calculation would be as shown in the table “Estate’s Net Tax Liability With More Than $1 Million Exclusion.”

Estate’s net tax liability with more than $1 million exclusion

PORTABILITY OF THE APPLICABLE EXCLUSION AMOUNT

An important estate tax provision available only to married couples is that the unused basic exclusion amount of a deceased spouse (the deceased spousal unused exclusion amount, or DSUE amount) is portable; it carries over to the surviving spouse if the executor of the deceased spouse’s estate makes an election (known as a portability election) on the estate tax return that the DSUE may be taken into account by the surviving spouse (Sec. 2010(c)(4)). Portability applies to the estates of decedents who die after Dec. 31, 2010.

Portability means that when a spouse dies with an estate tax base that is less than the basic exclusion amount ($5.49 million for 2017), the unused portion of the exclusion amount can be transferred to the surviving spouse. If portability is elected, the surviving spouse’s applicable exclusion amount is his or her own basic exclusion amount plus the DSUE (Sec. 2010(c)(2)).

Example 2

Assume that the individual in Example 1 with an estate tax base of $10,000,000 was a surviving spouse whose spouse predeceased him in 2017 and had an estate tax base of $2,500,000. His spouse’s estate has no estate tax liability because her estate tax base of $2,500,000 was less than the basic exclusion amount of $5,490,000.

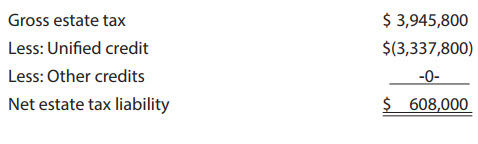

Portability allows her DSUE of $2,990,000 ($5,490,000 — $2,500,000) to be carried over to him. As a result, he has an applicable exclusion amount of $8,480,000, consisting of his basic exclusion amount of $5,490,000 plus her DSUE of $2,990,000. As in Example 1, his tentative estate tax and gross estate tax is $3,945,800; however, his unified credit takes into account the portability of his deceased spouse’s unused exclusion amount and is $3,337,800 as shown in the table “Tentative Estate Tax and Gross Estate Tax.”

Tentative estate tax and gross estate tax

Assuming there are no credits other than the unified credit, his estate would have a net tax liability of $608,000 as shown in the table “Net Tax Liability With No Credits.”

Net tax liability with no credits

With portability, his estate tax has gone down by $1,196,000 ($1,804,000 — $608,000), which is the DSUE of $2,990,000 multiplied by 40%.

As discussed previously, a much simpler way to calculate his estate tax is by subtracting the applicable exclusion amount from the estate tax base and then multiplying that amount by the highest marginal estate tax rate of 40%. The calculation would be as shown in the table “Simplified Calculation of Estate Tax.”

Simplified calculation of estate tax

PLANNING AND LOOKING AHEAD

With the large, inflation-adjusted estate tax exemption amount and portability, fewer taxpayers are subject to estate taxes. Nonetheless, making the portability election and using various estate planning techniques may require estates that might not be subject to the estate tax to file an estate tax return. Proper use of portability and the availability of other estate planning techniques make it important for taxpayers to seek professional advice.

Part 2 of this article in the November JofA will examine how to maximize the marital deduction, family trusts, irrevocable life insurance trusts, qualified personal residence trusts, and the importance of having a will.

About the author

David J. Beausejour (dbeausej@bryant.edu) is a professor of accounting at Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I., where he teaches taxation, personal financial planning, and wealth management.

To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Sally P. Schreiber, senior editor, at Sally.Schreiber@aicpa-cima.com or 919-402-4828.

AICPA resources

Articles

- “Planning Opportunities for the Final Tax Return,” JofA, July 2017

- “What All CPAs Should Know About Elder Planning,” JofA, July 2017

Publication

- The CPA’s Guide to Financial and Estate Planning (#PPF1702D, online access)

CPE self-study

- Estate & Trust Primer—Tax Staff Essentials (#157754, online access; #GT-TSE.ETP, group training)

For more information or to make a purchase, go to aicpastore.com or call the Institute at 888-777-7077.

The Tax Adviser and Tax Section

The Tax Adviser is available at a reduced subscription price to members of the Tax Section, which provides tools, technologies, and peer interaction to CPAs with tax practices. More than 23,000 CPAs are Tax Section members. The Section keeps members up to date on tax legislative and regulatory developments. Visit the Tax Center at aicpa.org/tax. The current issue of The Tax Adviser and many other resources are available at thetaxadviser.com.

PFP Member Section and PFS credential

Membership in the Personal Financial Planning (PFP) Section provides access to specialized resources in the area of personal financial planning, including complimentary access to Forefield Advisor. Visit the PFP Center at aicpa.org/PFP. Members with a specialization in personal financial planning may be interested in applying for the Personal Financial Specialist (PFS) credential. Information about the PFS credential is available at aicpa.org/PFS.